‘60s Muse Turned Psychologist Jenny Boyd Explores Rock’s Greatest Icons

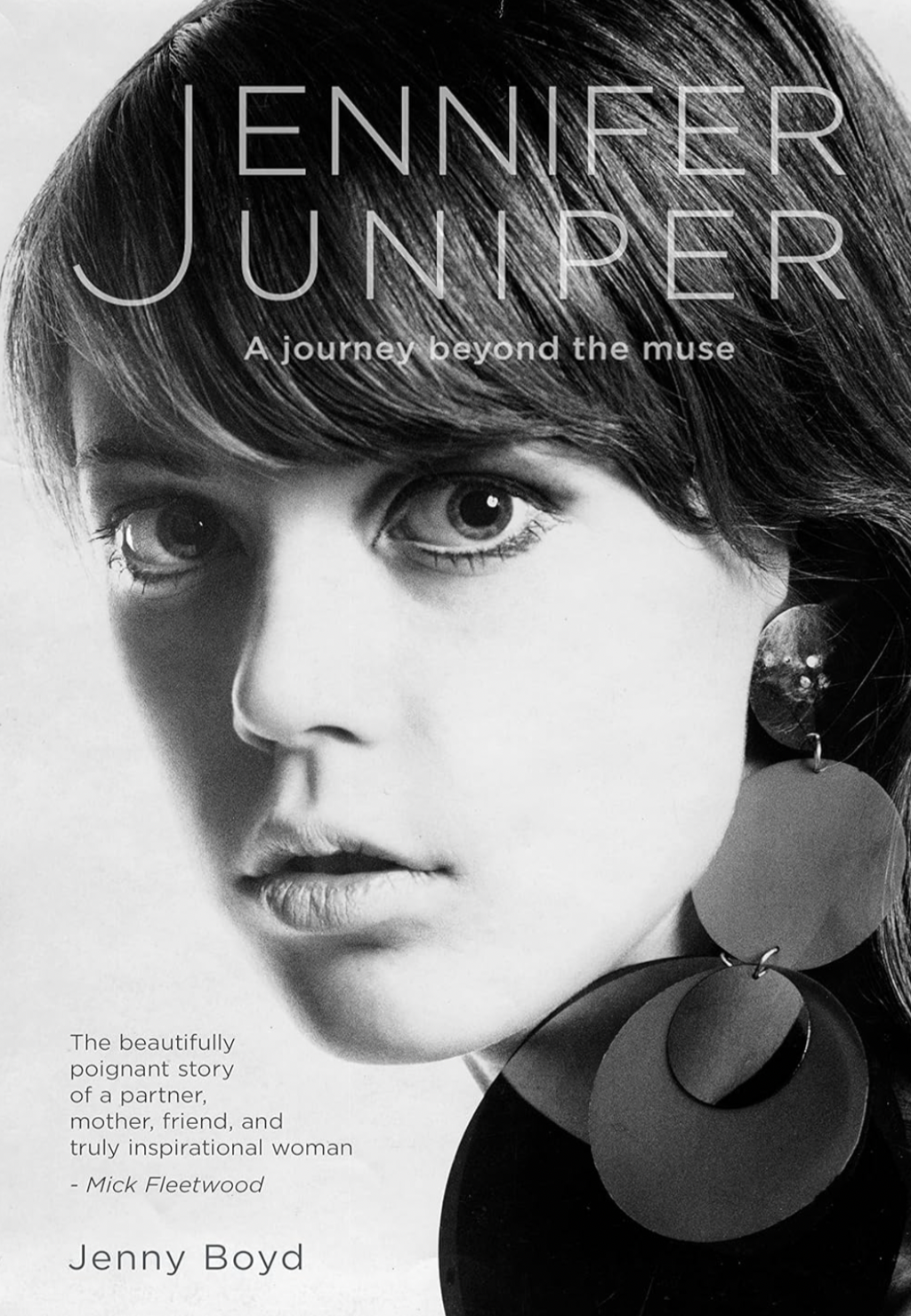

There is a whole layer of iconic women who are brilliant and accomplished, but they’re mainly known for their association with iconic men. Jenny Boyd is one such woman who first was known as being the little sister of Pattie Boyd (Mrs. George Harrison and, later, Mrs. Eric Clapton). Boyd eventually became known for her own rock star associations. She’s the titular person in Donovan’s “Jennifer Juniper,” which he wrote to woo her (unsuccessfully). Mick Fleetwood was successful in snagging her. He married her–twice. I would venture as far as to say the “Camila” character in Daisy Jones & the Six is loosely based on Boyd. After splitting from Fleetwood, Boyd married yet another drummer, Ian Wallace (King Crimson, Bob Dylan, Don Henley). These personal experiences are gathered in her 2020 autobiography, Jennifer Juniper: A Journey Beyond the Muse.

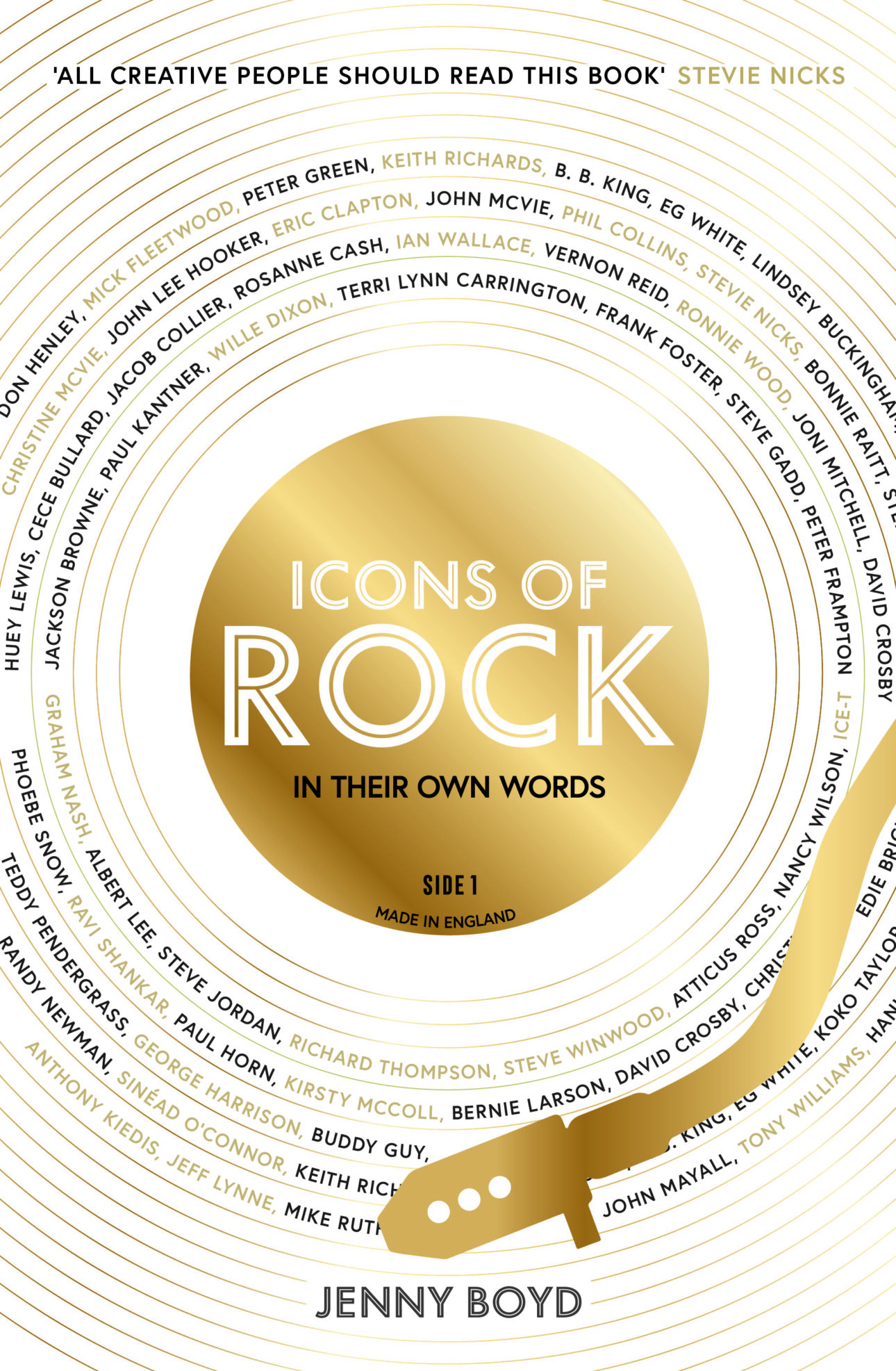

Boyd is more than a trophy wife, however, always seeking her own identity separate from that of her partners. She went back to school in the late ‘80s and earned her PhD in psychology. She authored Musicians in Tune: Seventy-Five Contemporary Musicians Discuss the Creative Process, which was published in 1992. In it, Boyd taps into her impressive network of rock stars, among them, George Harrison, Mick Fleetwood, Don Henley, Sinéad O’Connor, Eric Clapton, Keith Richards, Ravi Shankar, Nancy Wilson, Ice-T, Peter Frampton, Joni Mitchell, Ringo Starr, Anthony Kiedis, Buddy Guy, Rosanne Cash and on and on. The list is jaw-dropping. Boyd interviews 75 musicians about their creative process, organizing their responses into topical chapter headings. In return, they reveal details to her as a scholar and a counselor, but also as a friend, which is where she has the advantage over most of us music scribes. In 2014, the book resurfaced in the UK as It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll: Iconic Musicians Reveal the Source of Their Creativity.

The book received yet another rebrand in 2023, repackaged as Icons of Rock – In Their Own Words: From Eric Clapton to Mick Fleetwood, Joni Mitchell to George Harrison, an intimate portrait of their craft, publishing in the US this year. In this refreshed version, the content is organized by musician, with each one getting their own chapter speaking about the range of topics the prior version had as topic headings. Furthermore, a handful of present-day musicians are included, among them, Jacob Collier and Atticus Ross. Boyd was able to revisit the interviews she did some 35 years ago. In some cases, she updated them with current conversations with the same artists and had them reflect on what they said all those years ago. In other cases, such as with her departed friends Christine McVie and George Harrison, she puts their input into the context of the current time.

Icons of Rock is like a podcast in book form, and if you listen to the audiobook, it is like a one-person narrative podcast, with Boyd reading the interviews. In certain chapters, the musicians themselves speak, their parts taken from Boyd’s interview tapes. The book provides an insight to the creative muse, working process and emotional impact. It doesn’t shy away from speaking about substance use and abuse, its influence on creativity and its drawbacks. Musicians speak candidly about the positives and negatives of fame, what their daily lives are like and how they remain inspired.

“I’m quite shy,” Boyd reveals when we speak ahead of the book’s domestic release. “But this was my first big research and I was just so into it. When it’s something like musicians and creativity, it’s slightly magical.”

SPIN: Considering you knew many of the musicians in your book socially, what were their attitudes toward you as an interviewer?

JENNY BOYD: They were amazing. They were so into it. This was 35 years ago so people weren’t asking musicians questions like this then. It was, “What did you have for breakfast?” They were relieved it wasn’t that sort of thing and that it was really thought-provoking. Often, at the end, they’d say, “I feel like I’ve been in a therapy session,” or, “That’s the best interview I’ve ever done.” I think they were surprised, but really into it.

Because most of them were friends, most of them knew my background, and also having just finished the Master’s in counseling/psychology, I knew when to slow down and when to stop when there was an awkward silence and let them continue. Little things I didn’t mean to do seemed to work.

As far as the artists being forthcoming, did you feel there was a difference between the artists you already knew and the ones you didn’t?

I’d never interviewed people before. Don Henley was my first interview. I’d seen him a lot with the band because my then husband was playing with him. If they were touring England, we’d be in a pub with him chatting with everybody. Somebody would say something funny. It was a group thing. I never sat with him, just him and me. Once I got into the swing of it, I loved it.

Even the ones I knew, say John McVie of Fleetwood Mac, I’ve known him for years and years. We all lived together in Hampshire. He’s always been quite quiet. When I interviewed him, there he was saying this real soulful stuff. It’s another side of John.

A lot of them, I’d know them well in a group situation, but hadn’t sat with them and asked these questions. What would Stevie [Nicks] say if we just sat on a sofa, and we talked about all this? She loved it. She went off. Or Joni Mitchell, all the stories that kept coming out, like a storyteller. I could have kept on going year after year after year. I would have loved doing that.

How was the interview process different for you with the newer artists and were their responses different to the musicians from a few decades ago?

The new ones were to show people and me, I’m interested, what the music world is like today. Their creativity is the same. They still go into this “zone.” But when they write songs, they don’t usually write by themselves or just one other person. You send it to one person to put the drums on, you send it to another person to do the guitar, and then the vocal. It’s all spread out like that. That’s very different. It’s more contrived.

Were there any bucket list musicians you were not able to interview?

Not then [in the original interviews]. What was more difficult was getting the musicians now because they don’t have a manager. They have teams. I wanted Phoebe Bridgers. Someone I know knows her mother very well. I managed to get through to her mother. Her mother asked Phoebe and Phoebe said, “Oh, I’d be honored to.” But then we had to do it through the manager. The manager didn’t answer back for two, three months. I went back to the mom saying, “Any news? Can we do Phoebe?” Then finally the manager responded, “Oh, no. She’s very busy.” So Phoebe didn’t have a say. It was slightly annoying because she wanted to do it. It was very different.

Joni Mitchell…I knew Peter Asher who was her then manager from the ‘60s. It was easy to say to Peter Asher, “Can I interview her?” “Oh yeah, it’s easy.” Somehow, I knew somebody or maybe not. I don’t know how I got a hold of BB King.

I went to Willie Dixon’s house. That was so nice. We sat in his sitting room and it was so great. The energy was wonderful. There was a blues concert not long afterwards in New York. He was there. He can’t walk very well so he walked on stage with a stick. As soon as he started singing, the stick went up and he was like dancing with it. He died a few months later. When they’re in that zone, they can do anything.

When my husband Ian would go out with Bonnie Raitt, I’d see Bonnie backstage going, “Oh, my stomach.” And then I would go up the front and they’d be on stage and she’s being sexy and doing all her stuff and you would never know. It probably was fine. Because that’s it. It’s such a powerful thing.

There is one more person I want to interview, and that’s Rick Rubin. I’ve sent him my books. In the letter I said, “I’d love to interview you.” I haven’t heard anything from him. I don’t even know if he even saw it. But that’s all you can do. There’s something about waiting things out. At the right time, something will happen because I can get a little impatient. I have to learn to step back a bit and see how it goes.

Are there any anecdotes from the interviews that you can share?

There was one that was really sort of embarrassing and it never got into the book. I was still pretty new at it. It was before I’d gotten used to it. I managed to contact Eric Burdon. He came to this studio place. He was talking about the days when he was really big. He had a great voice. I asked, “Can I take a photograph of you?” He was standing there doing his hair and everything. I clicked and said, “Oh, there’s no film in here. I’m so sorry.” I don’t know what happened to that tape. It was at the beginning, when I was kind of fumble-y and bumble-y.

When I was interviewing George [Harrison]—which I say in the book—he had been out the night before playing, and that’s the beginning of the Traveling Wilburys. Before that George would be at home doing his gardening. I asked him the question about drugs and alcohol. And he said, “Yeah, I think every now and then, it’s good to have a beer or two. In fact, last night I had a beer or two with Bob Dylan and Jeff Lynne and Tom Petty, and we all played together and it was so brilliant and wonderful. And so sometimes it’s good.” I realized years later when I was listening to this interview, “I think he was hung over but never said.” He was a recluse in England. In the end, he said, “Oh, it was so nice being interviewed by you.” I’d been like his little sister in a way. I’d seen him many times, either in LA, or [with] Pattie and I’d go around to the house and chat with him.

Link to the source article – https://www.spin.com/2024/02/60s-muse-turned-psychologist-jenny-boyd-explores-rocks-greatest-icons/

Recommended for you

-

Oscar Schmidt OM40LH Left Handed F-Style Mandolin, Tobacco Sunburst Lefty

$0,00 Buy From Amazon -

Bass Glarry GIB Electric 5 String Bass Guitar Full Size Bag Strap Pick Connector Wrench Tool Sunset Color

$119,99 Buy From Amazon -

LEKATO Guitar Headphone Amp, Micro Guitar Headphone Amplifier for Electric Guitar & Bass Rechargeable Headphone Amp Guitar Practice with 5 Effects(Clean Chorus Overdrive Distortion and Wah)

$36,99 Buy From Amazon -

Squier Affinity Series Stratocaster Electric Guitar, with 2-Year Warranty, Lake Placid Blue, Maple Fingerboard

$249,99 Buy From Amazon -

Roland UM-ONE-MK2 One in Two Out Midi Cable

Buy From Amazon -

Cable Guy – Banjo Kazooie

$34,00 Buy From Amazon -

Novation FLkey Mini – Portable 25-Key, USB, MIDI Keyboard Controller with FL Studio Integration for Music Production

Buy From Amazon -

Case Compatible with Otamatone [English Edition] Japanese Electronic Musical Instrument Portable Synthesizer, Instrumental Music Toy Storage Holder for Otamatone Regular Size (Box Only) (Black)

$16,99 Buy From Amazon

Responses