How the White Stripes and the Hives built on the legacy of garage rock

Two U.K. televisual musical moments from the turn of the century, both involving stripped-down young rock ‘n’ roll bands:

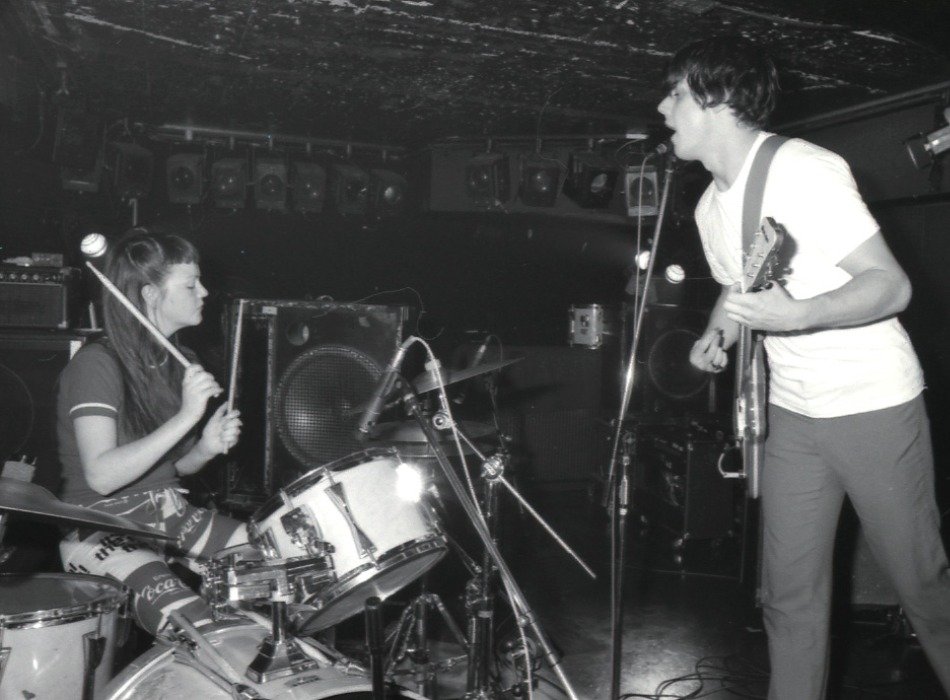

First up, the White Stripes on long-standing U.K. pop showcase Top Of The Pops, in February 2002. “Fell In Love With A Girl” began its chart-shaking international climb, and Jack and Meg White entered English living rooms for the first time. They refused to obey the show’s strict lip-synching policy, ripping through their single live, with a manic rawness bridging Ramones and Little Richard. Midway through, Jack signaled his ex-wife to switch up the beat to a four-on-the-floor, kick-drum-and-high-hat pattern. He improvised a brief sermon about the advantages of love, quoting Cole Porter and some unidentified bluesman along the way. Just as swiftly, they returned to their hit. TOTP’s studio audience was gobsmacked.

Crossfade to three months earlier, on Later… With Jools Holland: Swedish upstarts the Hives assaulted the venerated talk show with their new single “Hate To Say I Told You So.” Over the course of the next year, this compression of the Kinks’ early distorto-rock a la “You Really Got Me” conquered the world. The look in Howlin’ Pelle Almqvist’s eyes as his bandmates detonate those four now-familiar chords, while he tosses his mic hand-to-hand, awaiting his cue, is basically, “Yeah, I’m gonna have you yet.”

“We are the Hives! We’re from Sweden,” he announced, as the arrangement dropped down to Dr. Matt Destruction’s four-wheel-drive bassline. “Wanna know how to spell the Hives? G-E-N-I-O-U-S — the Hives!” England was charmed.

You have to wonder if any viewers or studio audience members were aware or cared that both bands were reaching for the same moment in rock history?

Read more: These 10 artists made Washington DC into one of the epicenters of punk

Garage punk went commercial for the second time in its long history during the 21st century’s beginnings. It was a welcome antidote to the day’s abysmal rock and pop — a noisy, aggressive, high-energy music simple enough for any kid with minimal equipment and basic ability to replicate. Punk rock began with garage in the ’60s. Now it returned to put rock ‘n’ roll back in the hands of common folk. This is the story of the most liberating sound around, full of teenage hormones and sheer joy. Enjoy our custom playlist as you read.

“I’m five years ahead of my time!” – In the beginning…

Feb. 9, 1964: The Beatles appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show for the first time. The next day, at high schools across America, it seemed as if every teenage boy had washed the Brylcreem out of his hair and combed it down, hanging it as far in his eyes as his haircut allowed. Every girl might have scrawled “I luv Paul” on her notebooks. That afternoon, musical instrument shops in every U.S. city were desperately reordering electric guitars, amps and drums.

Garages in every neighborhood soon reverberated with rudimentary bands working out “I Saw Her Standing There” and “Twist And Shout,” dreams of Beatlemania dancing in their heads. Those makeshift practice spaces obviously gave these bands a name in later years. But this impulse existed prior to the British Invasion, in the form of teen combos working sock hops and frat dances, playing dirty instrumentals thick with overblown saxophones and reverb-drenched guitars. The hairy, hydra-headed beast of John, Paul, Ringo and George changed the musical and aesthetic focus.

The Beatles’ musical sophistication eluded the capabilities of most kids’ uncalloused fingers. The crude bashing of some of the British acts following in the Fab Fours’ wake — the Kinks, the Yardbirds and especially the Rolling Stones — proved more accessible. All deployed an aggressive take on American R&B, their Vox AC30 amps pushed into harmonic overload to compete with screaming teenage audiences. When Stones guitarist Keith Richards distorted “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction’s” three-note motif with a Maestro Fuzz-Tone, fuzz replaced dirty saxes as every garage band’s signature. British bands amplified the blues’ inherent aggression. Their American disciples amplified the aggression further.

As Yardbirds manager Giorgio Gomelsky remembered in 2001: “The Yardbirds played all across America in 1965. When we came back six months later, every local band was the Yardbirds!”

Read more: These punk records from 2000 led the genre into a brand-new century

He’s right. Dig “Psychotic Reaction,” San Jose’s Count Five’s sole hit single. It’s the greatest Yardbirds record the Yardbirds never recorded. They numbered among an elite group of garage bands who broke past local stardom, landing at least one single nationally: The Kingsmen’s “Louie Louie,” the Standells’ “Dirty Water,” “Pushin’ Too Hard” by the Seeds, “We Ain’t Got Nothin’ Yet” by the Blues Magoos, “96 Tears” by Question Mark & The Mysterians (featuring that other ‘60s garage instrumental mainstay, the wheezy Vox or Farfisa organ). Some of the rawest, best bands — such as Seattle’s Sonics, arguably the first punk band in the form we know — couldn’t chart with chaotic crunchers a la “He’s Waitin’.” Others, including Austin, Texas’ 13th Floor Elevators, applied LSD experimentation to their raunchy sounds on the glorious “You’re Gonna Miss Me.” That strain became known as psychedelia.

The Garage epoch blipped on rock’s timeline, though it’s arguably the music’s very essence. Most bands lasted as long as graduation or the draft allowed. But fuzz-toned echoes of that blip rang into the following decades.

“You’re gonna miss me, baby” – Nuggets and the ‘70s

The ‘70s initially resembled an army of James Taylors armed with acoustic guitars, strangling the life out of music. Then there were so-called “rock” bands with no roll, playing endless guitar and drum solos onstage. It felt as if you needed to enroll at a conservatory just to buy a Les Paul. Where was the excitement of just six years before? Or of 1956? No wonder Iggy And The Stooges and the New York Dolls had to happen!

It didn’t escape a cadre of rock journalists — Lester Bangs and Dave Marsh at Creem, Greg Shaw at Who Put The Bomp?, Lenny Kaye — that the Dolls and Stooges were possibly the last garage bands, Marshall amps relacing Vox’s. They longed for scratchy old 45s of “Dirty Water” when shutting their radios off on “Fire And Rain.” Nostalgic articles such as Bangs’ “Psychotic Reactions And Carburetor Dung” rhapsodized the garage moment. Marsh named the sound “punk rock” in describing Question Mark & The Mysterians in 1969. He inadvertently named rock’s next revolution.

Read more: Why Green Day’s 1994 BBC Sessions sound better with a cup of coffee

Elektra Records’ Jac Holzman charged Kaye with assembling an oldies collection. The future Patti Smith Group guitarist delivered a codification of ‘60s garage — Nuggets: Original Artyfacts From The First Psychedelic Era 1965-1968. Across two LPs, it encompassed everything from hits a la “Psychotic Reaction” and the Knickerbockers’ raunchy Beatles approximation “Lies” to such obscurities as “Run, Run, Run” by the Third Rail. This was no K-Tel oldies sampler. This was a taste and style, carefully curated, the first serious recognition of garage impulses.

Kaye called it “punk rock” in his liner notes. “Garage rock” became the signifier later in the decade, once punk-as-we-know-it arrived in the mid-’70s. But Nuggets entered the record collections of virtually every participant in first-wave punk’s 1975-1979 explosion. Television covered the 13th Floor Elevators, the Cramps recorded “Psychotic Reaction” among others, Suicide deconstructed “96 Tears” — the list is endless. Then came bands consciously giving garage a ‘70s makeover — Los Angeles’ Droogs, Boston’s DMZ (who resembled the Stooges playing Nuggets), even San Francisco’s Flamin’ Groovies. (Beginning as an original garage band in 1965 proved advantageous!) Perhaps the Ramones and the Sex Pistols were the Sonics’ revenge?

“Are you gonna be there when I set the spark?” – Garage enters the ‘80s

As Ronald Reagan was sworn in as America’s 40th president and the excitement of ‘77 punk gave away to the hyper assault of hardcore, factions of punk’s fanbase grew disenchanted. One of the directions their antennae divined? Garage punk.

Fanzines such as Mike Stax’s still-extant Ugly Things poured over the minutiae of these crackling old homemade singles, figuring out who manufactured the tubes powering the Misunderstood’s amps and other mystic arcana. Yet, more semi-legal reissue compilations of garage 45s flooded the market — Pebbles, Boulders, Rubble, Back From The Grave. A new wave of garage bands — now calling themselves garage bands — emerged, faithfully recreating the sound of ‘66, down to their buzzy antique Vox amps, Brian Jones haircuts and stovepipe corduroy trousers pulled over Chelsea boots. Be it L.A.’s the Unclaimed, NYC’s Fuzztones or Headless Horsemen, or even the relatively successful Fleshtones and Australia’s Hoodoo Gurus, all shook it down in a good, relatively faithful fashion.

Pride of place goes to Rochester, New York’s Chesterfield Kings and Boston’s Lyres, a DMZ offshoot. Alongside U.K. garage polymath Billy Childish’s 5,000,000 bands — Thee Milkshakes, Thee Mighty Caesars, Thee Headcoats and others boasting a King James edition definitive article — Chesterfield Kings and Lyres distinguished themselves with strong songwriting smarts and a rejection of garage revivalism’s cartoon/fashion aspects. These were solid punk bands, regardless of the ‘60s influences. Mightiest of all were Sweden’s Nomads, wedding 1966’s fuzz-tone thrust to modern metal amplification and ‘77 aggression. They’re the ‘80s garage kings.

Read more: Revisit ‘Nimrod:’ the moment Green Day ripped up their own rulebook

“My love is stronger than dirt” – The ‘90s renovate the garage

Garage was no longer the Sound Of ‘66 Today, in the Nirvana/Bill Clinton era. The garage musicians of the 20th century’s final decade rejected the cartoon/fashion aspects of ‘80s garage revivalism almost wholesale. Rather, greaser and Tiki culture seemed to invade the garage scene, as bands more resembled ‘70s punkers: Leather jackets, ripped jeans, and gas station attendant shirts. As they dressed down, they also amped up. Bands such as Bellingham, Washington State’s Mono Men (whose leader Dave Crider also helmed prestigious modern garage label Estrus), Spokane’s Makers or San Antonio’s Sons Of Hercules owed as much to the Nomads or even the Replacements as the Standells. Even grunge heroes Mudhoney flashed intensified garage influences. There was also Detroit’s bass-less sub-mod three-piece the Gories, almost reducing garage into a noisy, post-no wave din.

Then there were the Mummies, writhing about in filthy gauze bandages and attacking ramshackle cheap equipment, proudly reveling in the glory of the lo-fi raunch they called “budget rock.” They deliberately snubbed propriety, recording crude singles such as “Stronger Than Dirt” everywhere but studios. They rejected Sub Pop’s interest, expressing disgust with the “hippie heavy-metal label.” They named a singles collection Fuck CDs! It’s…The Mummies! Their example inspired such lo-fi garage-istas as Supercharger, the Rip Offs and Oblivians. Budget-rock’s apotheosis: Memphis destructo-punks the Reatards, featuring prodigy Jay Reatard.

“A seven nation army couldn’t hold me back” – Garage in the 21st century

NYC’s the Strokes supercharged traditional garage with Velvet Underground-esque angular ‘60s punk-isms and the ‘70s Lower East Side’s artier side. Then they sold England on the fact that they were The Next Big Thing. It worked. Debut album Is This It launched in the U.S. one month after 9/11, its single “Last Nite” democratizing radio and MTV. The door knocked off the hinges, Detroit’s White Stripes walked through, followed by the Hives, the Vines, the Datsuns and other bands with/without definitive articles. None were Count Five revivalists.

The White Stripes’ glory reflected momentarily on their hometown, the Von Bondies, the Go, the Paybacks, Ko And The Knockouts and ex-Gories Mick Collins’ Dirtbombs squinting into the spotlight. In the U.K., the Libertines followed the Strokes’ blueprint for modern garage stardom, their literate, scrappy English interpretation of the Replacements now in vogue. British electric guitar sales skyrocketed briefly.

Jay Reatard leaped from the Reatards to the Lost Sounds, then seemingly a new band daily for years, until going solo mid-decade. Blood Visions entirely rewrote garage’s rules: Ornate songwriting a la Queen, played with hardcore’s vicious attack, recorded cheaply, remaining well produced. The entire world is still trying to catch up with his genius.

Read more: The 10 best punk drummers of the 1970s displayed great skill and power

Jack White parlayed the dissolved-since-2010 White Stripes’ success into a cottage industry all his own: bands such as the Raconteurs and the Dead Weather, and his own solo work. It all centers around his Third Man business empire, the label and his record stores helping restore the luster of vinyl. His own music skews less garage-y as time has advanced, though it remains ineffably rock ‘n’ roll.

The Jim Jones Revue crashed the piano-banging spirit of the ‘50s into lo-fi garage in the ‘10s. Ireland’s teenage Strypes beelined to garage’s source material — ‘60s British R&B a la the Yardbirds — for their inspiration. Garage’s ‘20s spirit manifests in Sweden’s the Maharajas, or French fuzz brutarians Les Grys-Grys. Garage is a never-dying rock ‘n’ roll strain. If budding musicians need to make a basic, fun, hormone-drenched racket requiring fuzzboxes? Garage punk thrives. And it feels like this!

Thanks to Ugly Things editor/Loons frontman Mike Stax for his garage expertise.

The post How the White Stripes and the Hives built on the legacy of garage rock appeared first on Alternative Press.

Link to the source article – https://www.altpress.com/features/garage-rock-punk-rock-1960s-the-white-stripes/

Recommended for you

-

SAYULI MIDI Cable, 1.5m/5Ft USB 2.0 Type B OTG Cable to iOS Devices, Compatible with iPhone, Midi Controller, Electronic Music Instrument, Midi Keyboard, Audio Interface, Printer

$10,99 Buy From Amazon -

PreSonus Studio 26c 2×4, 192 kHz, USB Audio Interface with Studio One Artist and Ableton Live Lite DAW Recording Software

$0,00 Buy From Amazon -

Golden Gate B-107 Vintage Electric Bass Guitar Tuners – Set of 4 – Nickel

$27,95 Buy From Amazon -

B&C ME60 Studio Subwoofer

$94,00 Buy From Amazon -

Electric Bass Guitar 4 Strings Full Size P Bass Beginner Kit Black for Starter with Gig Bag, Guitar Strap, and Guitar Cable (4) (4S)

$200,97 Buy From Amazon -

Hartke HD15 Bass Combo Amplifier

$129,99 Buy From Amazon -

KRK S10.4 S10 Generation 4 10″ 160 Watt Powered Studio Subwoofer (Renewed)

$0,00 Buy From Amazon

Responses