‘Speaking in Beads’ with Jenny Shuman

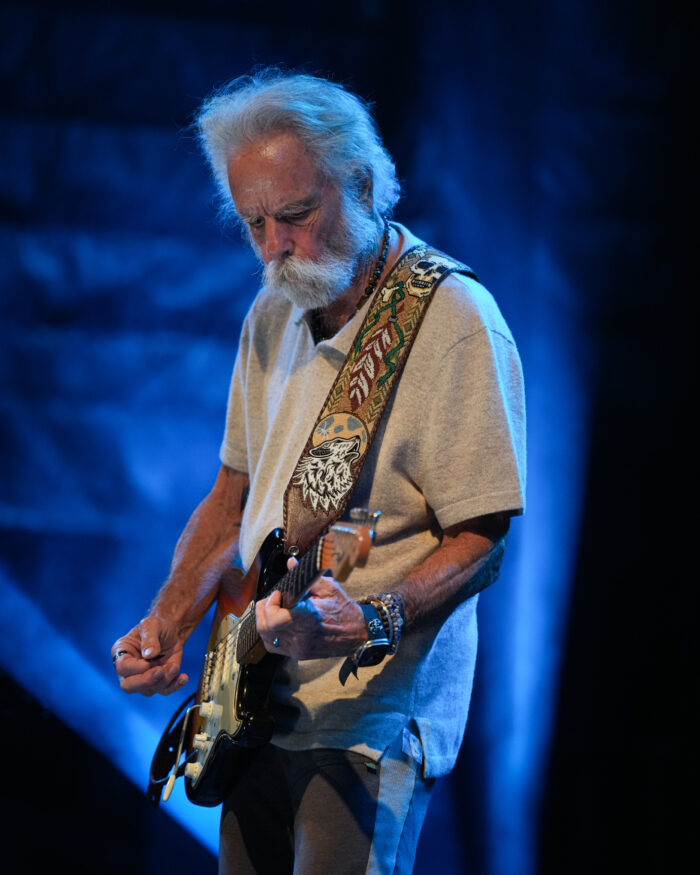

Photo Credit: Jay Blakesberg

Jenny Shuman’s story is one of fate and a bit of magic. In her book Speaking in Beads, Jenny describes coming of age in the early ‘90s, watching her peers travel show to show, seeking any and all opportunities to see the Grateful Dead. She juxtaposes that time-honored musical experience with her own participation in the traveling Powwow circuit, where she honed her craft and amassed the skills that continue to inform her work.

Jenny beads guitar straps. She received her first loom at 17, and with time and significant practice, she has reached master status.

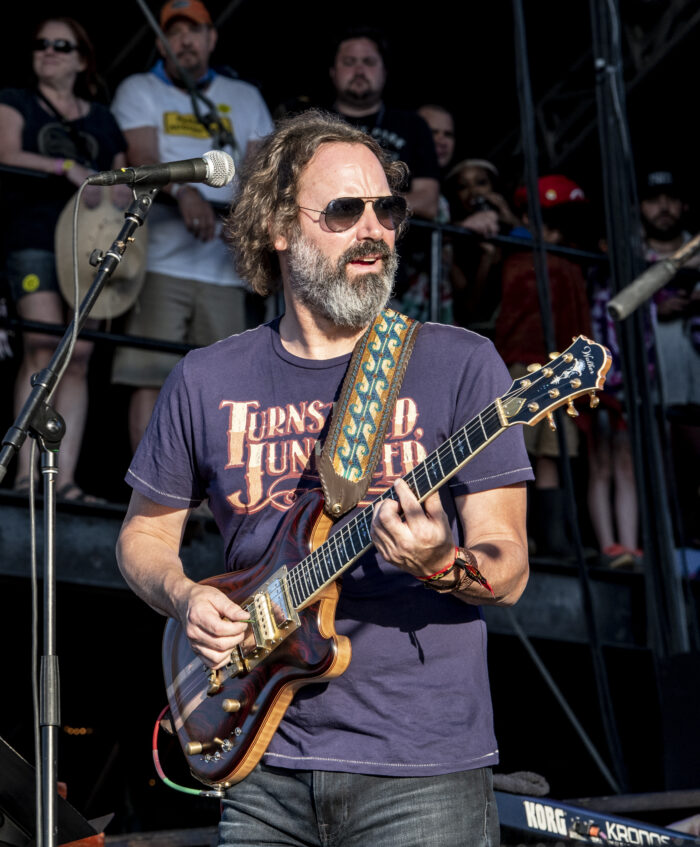

Bead by bead, she carefully produces motifs and generates narratives that speak to her clients’ essence and experiences. In the following interview, Jenny shares her background on the loom and stories of the artist relationships she has forged while adorning the shoulders of greats, such as the late Phil Lesh, Bob Weir, Oteil Burbridge, and so many more.

Ahead of the holiday season, Jenny conversed about her work, drawing on the content from her debut 200+ page coffee table book, Speaking in Beads.

In Speaking in Beads, you write about traveling the Powwow circuit and the community practices you learned, such as the loom, which you continue to use when creating guitar straps today.

I’ve always been artistic, whether writing or sketching. Doing latch hook or crocheting with my grandma–it was always nurtured in different ways–but it wasn’t until I was 17 that I got my first loom.

It was Powwow where I learned from the elders all the rules: Don’t pull too tight; pull tight enough. Only one knot in any piece of loom work, and the rest is weaving—all the tricks of the trade. However, the spiritual aspect has become an integral part of everything I do. You cannot remove the spirit from my work. And it was at Powwow where that was really solidified. It was a place to set yourself back and open that space between that ethereal plane because it’s not just my vision, and it isn’t just their vision; it’s that coming together.

So, it was at the Powwow that I was taught to honor the spirit in all that we do. That opened up an entire capability, or resource, if you will, for the expansion of imagination. Because I grew up in Michigan, it was traditional woodland design rather than simple geometrics. It taught me to go off the page, step outside the boundaries, and add curves, which took a long time. I’m still learning, but many Three Fires traditions taught me to take it beyond the simple, beautiful, straight lines. It was there (Powwow) that I learned to embrace that spiritual side of things where everything is possible.

Keeping with the conversation’s spiritual currency, you describe guitar straps as energy vessels. Can you unpack the transfer of vibrations during a performance and how the strap feels afterward?

It absolutely has a completely different vibration than a lot of things. A beautiful guitar strap, no matter who weaves it, has energy. Because of that spiritual space I share with my clients, it is of another dimension that just comes through. I’m fortunate and honored enough to be that vessel that has been chosen to produce these beautiful living artifacts where I can speak for them and how I interpret them. I’m just a normal girl dancing in the crowd, so it’s also speaking for all of us.

It’s interesting because they also change energy, so when I take it off my loom, and I’ve been working with them, it’s been in my hands, and then they go to the musician, and they do shift. The first time I noticed it so poignantly was with Oteil’s very first strap. I needed to make an adjustment on the little adjuster part, and I picked up his green strap, and I thought, “Wow, this is really pretty.” I saw it as though it wasn’t mine. Which is weird cause it was. I had spent all this time with it, but the energy had significantly shifted to him. It was all because it had transferred 100% of his energy.

And they do vibrate. They’re part of our journey as people enjoy the music. It’s part of our journey because it holds that focus for some aspects of the concert–obviously not all parts of the show, but parts of it where you might open your eyes and go “Woah,” and the beat strikes you like a glitter ball.

Photo: Jay Blakesberg

In the book, you mentioned overlaps between musical and ceremonial communities. How do you find they relate?

[They are] spaces for group acceptance. It’s very similar because we gussy up for a show, put on our patches or our [tie] dyes or whatever speaks of that culture. We’re not worrying about how we look compared to other people; it’s just feeling, expression, and spirit. And when you leave you’re renewed. Particularly with the Grateful Dead because it is a counterculture of its own in terms of expression and spirituality–just owning yourself and celebrating independence and autonomy.

At Powwow, you smell sage and sweetgrass for days, and at a show, you probably smell some B.O. and patchouli for days. [Laughs.] The senses and expressions are different, but really, it’s such a similar line of celebration and connection to spirit and togetherness–having that common ground with everyone and coming together is everything.

You’ve demonstrated various methods for creating beaded patterns and iconography that adorn the straps. Can you explain some of your methods?

For applique: Oteil’s “From Egypt” strap, the very front wolf part of Bob Weir’s strap, or the “Mission Control” bass strap that was Phil Lesh’s. So, the applique is sewn directly onto the leather. There isn’t a loom involved. It’s kind of like cross-stitching needlework only with beads, where it’s one bead at a time; at most, you can put four on at a time.

You put the image directly onto the leather, or freelance it and follow the outline. You get that established, and then it’s just filling in with shading or detail. It is one bead down, and then you attach it. Then you come back up through the leather, go through that bead again, and then you add your next two, and you just keep building.

The thing about applique is that it’s a true point, or a true angle, or a true curve because there’s no graph work involved. It is simply the contour of the design without the barrier of lines and rows. It takes so much longer. It is very intensive, probably four times as much work, but it is worth it.

Whereas loomwork—which I’ve become pretty fluent in—you do have the barriers. That’s part of the challenge in getting the curve right. You’re doing spirals with rectangle beads; some are oblong, and you’re learning how to bend a rectangle.

Sometimes, the images are so detailed that I’ve learned to make a three-quarter profile of something rather than the whole image so that you get the suggestion of the piece or allow a fractal to go off the page where your brain gets to fill in the rest of the image because you know it’s there.

Each has its own challenge. I love a really good challenge, but I have to admit that if it’s not challenging enough, it’s like, “OK, we need to get through this.” As far as time goes, sometimes the design process is the longest one, and that can go from taking two to three days to dial in a design to months! Literally months.

Can you describe the process of creating a design with or for a client? One of the examples you use in the book is the strap you made for Bob Weir, which his wife and daughters commissioned.

In the case of Bob Weir, where it was Monet, Chloe, and Natasha lending their insight, how you see someone on stage can’t be removed from the equation. So there’s always a dynamic that is unique, and none of them are exactly the same. When it’s a gift for someone, in the case of Bob’s straps, it really is taking on all of what they want to be seen, and finding the most tasteful, elegant, aesthetic way to put that together so that there’s flow, finding a way for all of that to happen, while still honoring the regal natures of one’s stage presence.

And then there are times when people just open up, like Anders Osborne. He’s just so deep and he laid it out, and it took a long time for me to process that one because it’s just a lot to speak for him and all that he’s been through in a flowing way. So that one took months before I even had my first vision in order to tap into the design. And then it was some go-between until we nailed it. They know it’s right, because it feels right. It’s not just knowledge, it’s like this inner “Ahaa! This is it!”

Bob Weir’s 75th birthday strap has particularly poignant symbolism. What’s the story behind that piece?

Yes, that is so powerful. This one was all the girls, they all wanted to chime in and be a part of it. They wanted it to be a representation of the native designs he has an affinity for. It needed to be subtle because I didn’t want to take away from anything with so much going on.

They said he really loves the Jolly Roger skeleton versus the Grateful Dead one. He’s more like “Arrgh,” tough guy, pirate-skeleton. The girls wanted to be represented and they weren’t exactly sure how and in which way. After we spoke we decided that Bob was the good ol’ fashioned skeleton Jolly Roger, but Natasha should absolutely be Bertha, who is the matriarch of the Grateful Dead, if you will.

And then the feathers—because the red tailed hawk is community, it represents so many different things—so the two feathers on the side are the girls and then the one with the single feather is part of Bob’s majesty. So everybody was represented on that strap.

Then I was just like “OK, but we need something else in the front.” He looks like a werewolf, and Wolf Brothers, and when he sings he [howls]. So I drew the wolf and moon behind it. Women being Luna, and all of these girls represented on the strap with Bobby–that was how I interpreted it all.

Photo: Chloe Weir

Your ability to bead your client’s vision supports the continued claim that once they receive their strap, they feel more themself on stage.

Yes absolutely, and that’s sacred to them because as much as they give out, it’s also all that energy that’s coming at them, too. I mean can you imagine being the person in front of tens of thousands of people receiving all of that energy all of the time? It’s a zap!

And how they want to be seen and expressed is different for everyone. Like with Neal Casal—the woman who bought the strap as a gift to him had a lot of ideas about how she wanted it to be—but once we got him involved in the conversation, he said “I want it to be beautiful but super lowkey because, I’m the guy who just wears t-shirts on stage.” It took a while to get it right.

Photo: Jay Blakesberg

With the nature of the straps being so striking, I can imagine how word of mouth contributes to generating organic clientele.

It’s so funny, Amy Helm reached out and said, “I saw the straps Grahame [Lesh] and Elliott [Peck] from Midnight North have and I love it so much and I want one.” So I’m talking to her and I’m looking up Amy Helm and I’m like “Woah! This girl’s got talent!” And I’m just really jamming on it. Then we were talking one of the days and she was like, “I want my dad in the strap.” So I was like, “OK, so your dad was a musician and he played drums?” She said, “Stop. Stop everything. Do you really not know who my dad is?” I’m like, “Amy.. Helm… Get out!” [Laughs.] It’s like, put the dunce hat on me… She said, “No way. I am totally absorbing this moment because I haven’t had to explain who my dad is since I was a 12-year-old girl.”

So the pressure of creating an image that speaks to Levon Helm is a lot. Including her native heritage, I found a very traditional Choctaw design, but to fit her color aesthetic… We had taken a traditional design and took it outside of its traditional ways regarding something that would match her soft beauty. And deciding on representing her children literal, figuratively or uniform. Very personal aspects.

Is there a particular piece that stands out among the rest?

I love them all so much. I speak in the book about how everything is based on vibration. Whether it is sound vibration or love vibration–like you know when you’re around dark energy and how that feels? Or when you’re around loving, warm, open energy, how do you feel? And the same with relationships. How you’ve gotten to know somebody over time, and that evolution–that’s a vibration. And so the straps I’ve made for Oteil, knowing how they’ve evolved, the lines, the saturations, the inclusion of colors, the representation of the images, and the structure, have evolved so much from his first piece to his last. That green strap with the eagle feathers was made when I was first getting to know him and learning about his spirit in the material world this time around. I love that piece for that reason, and I love the last one because it’s the evolution of our relationship.

Link to the source article – https://jambands.com/features/2024/12/06/speaking-in-beads-with-jenny-shuman/

Recommended for you

-

PreSonus Temblor T10 Powered Studio Subwoofer – Free Cables XLR and 1/4 – (ProSoundGear Authorized Dealer)

$449,99 Buy From Amazon -

Alesis Quadrasynth – Large unique original 24bit WAVE/Kontakt Multi-Layer Samples Studio Library

$14,99 Buy From Amazon -

B50 5-String Banjo

$0,00 Buy From Amazon -

QuadCast Boom Arm, Mic Arm Microphone Arm for HyperX QuadCast SoloCast Blue Yeti Fifine AM8 and Most Mic, Mic Stand Desk with 3/8″ to 5/8″ Adapter by SUNMON

$26,99 Buy From Amazon -

Officially Licensed Michael Anthony Jack Daniels JD Bass Mini Guitar

$40,90 Buy From Amazon -

Froiny 1pc B Flat Bugle Call Trumpet Cavalry Horn Emergency Bugle Cavalry Trumpet with Mouthpiece for School Band

$22,65 Buy From Amazon -

from VIRUS B – Large unique original 24bit WAVE/Kontakt Multi-Layer Samples Library

$14,99 Buy From Amazon -

Roland RT-30HR Dual Trigger for Hybrid Drumming

$88,50 Buy From Amazon

Responses