TRUST ME, I’M A DOCTOR: Reverend Hunter S. Thompson, the Missionaries of the New Truth, and the Downfall of the Biggest Hallucinogenic Drug Factory in the Mid-West

And ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free.

John 8:32

I have a theory that the truth is never told during the nine-to-five hours.

Dr. Hunter S. Thompson

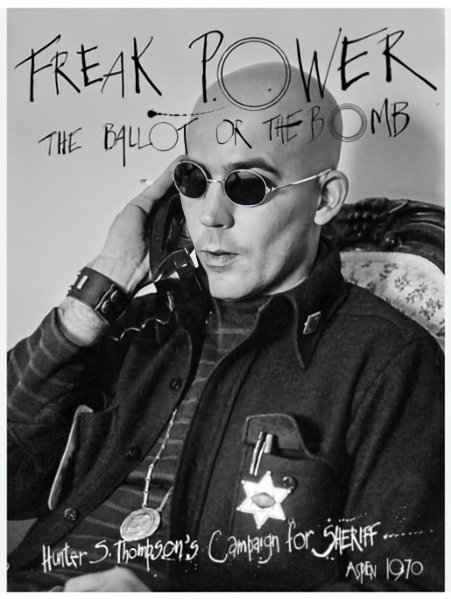

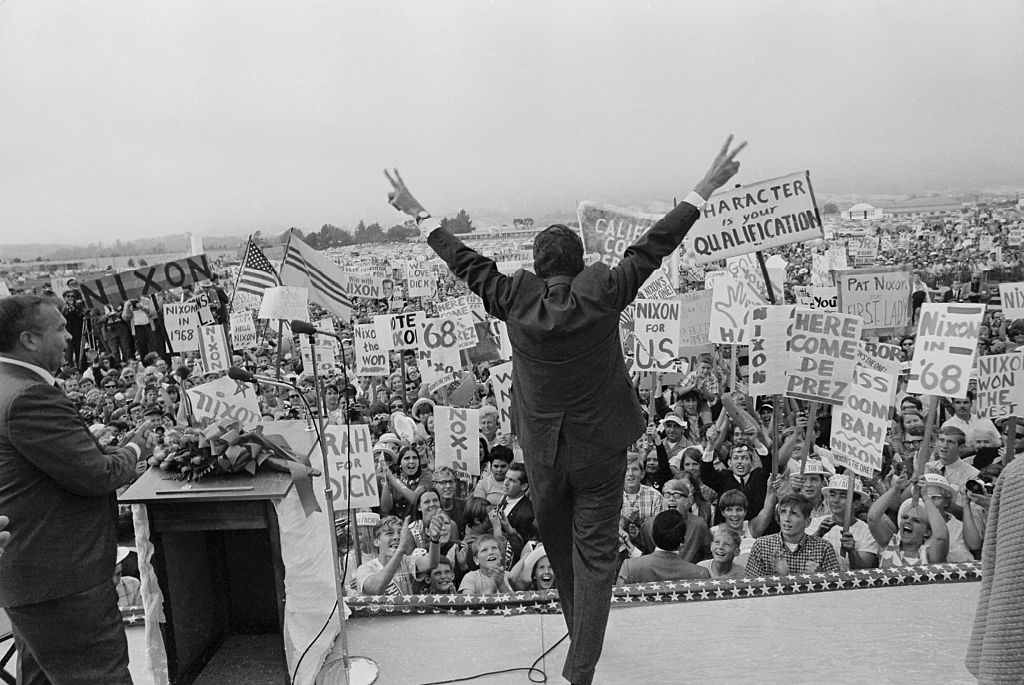

“Would you sell Peyote to this man?” That was the question emblazoned under a portrait of Hunter S. Thompson, candidate for Sheriff of Pitken County, Colorado, that featured on Aspen Wallposter No. 7, Fat City, USA in January 1971, in the aftermath of one of the most bizarre election platforms in the history of the United States.

“Dr. Hunter S. Thompson is shown here accepting a collect telephone call from Argentina in his Jerome Hotel headquarters two days before the deal went down,” read the accompanying text. “Dr. Thompson declined to comment on the nature of the call and later maced a wire service reporter who attempted to check it out through the switchboard. In this—the ill-tempered Freak Power candidate’s official campaign photo—he appears in full battle regalia: Gold-rimmed Greaser glasses, Magnesium police badge , 69th Infantry Division lapel flag, wireless wristband transceiver … and his silver Aztec “eternal life” pendant, a gift from Emiliano Zapata’s grand-daughter, Jilly.”

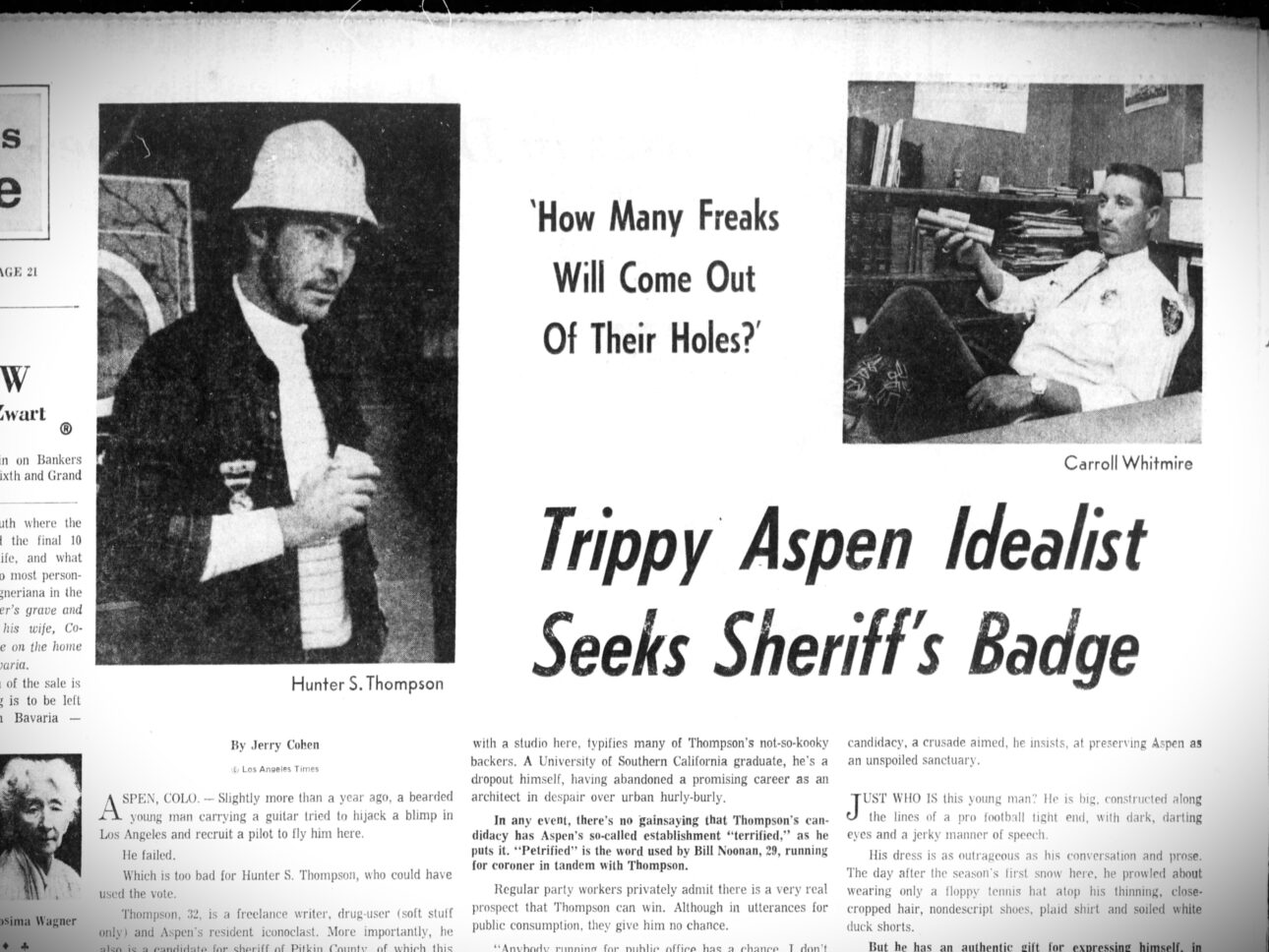

In reality, the pendant had been a gift from Oscar ‘Zeta’ Acosta, the Chicano lawyer, writer, and activist who was the real-life inspiration for Dr. Gonzo, the infamous ‘Samoan’ attorney in Fear and Loathing In Las Vegas. Earlier in the campaign, Thompson had been forced to shave his head bald after an ill-advised haircut went horribly wrong, largely due to the numerous joints shared between Thompson and his barber. He later joked that it allowed him to refer to the incumbent Republican Sheriff Carroll Whitmire as “my long haired opponent.”

Having been portrayed as a fascist ex-Hell’s Angel by the opposition in Aspen, Thompson decided to give them exactly that with his bizarre appearance, topped off with his ever-present cigarette holder and trademark white converse sneakers. He had also taken to writing a series of letters to the local newspapers in which he posed as Martin Bormann, the private secretary to Hitler who was then believed to have been sighted alive and well everywhere from Spain to Argentina. As Bormann, Thompson proposed all manner of increasingly ludicrous schemes to deal with the “hippie problem” in Aspen, including organizing a riot, to justify the purchase of large amounts of weapons by the Sheriff’s department, effectively lampooning the local conservative establishment. Each letter listed Thompson’s Owl Farm as Bormann’s residence.

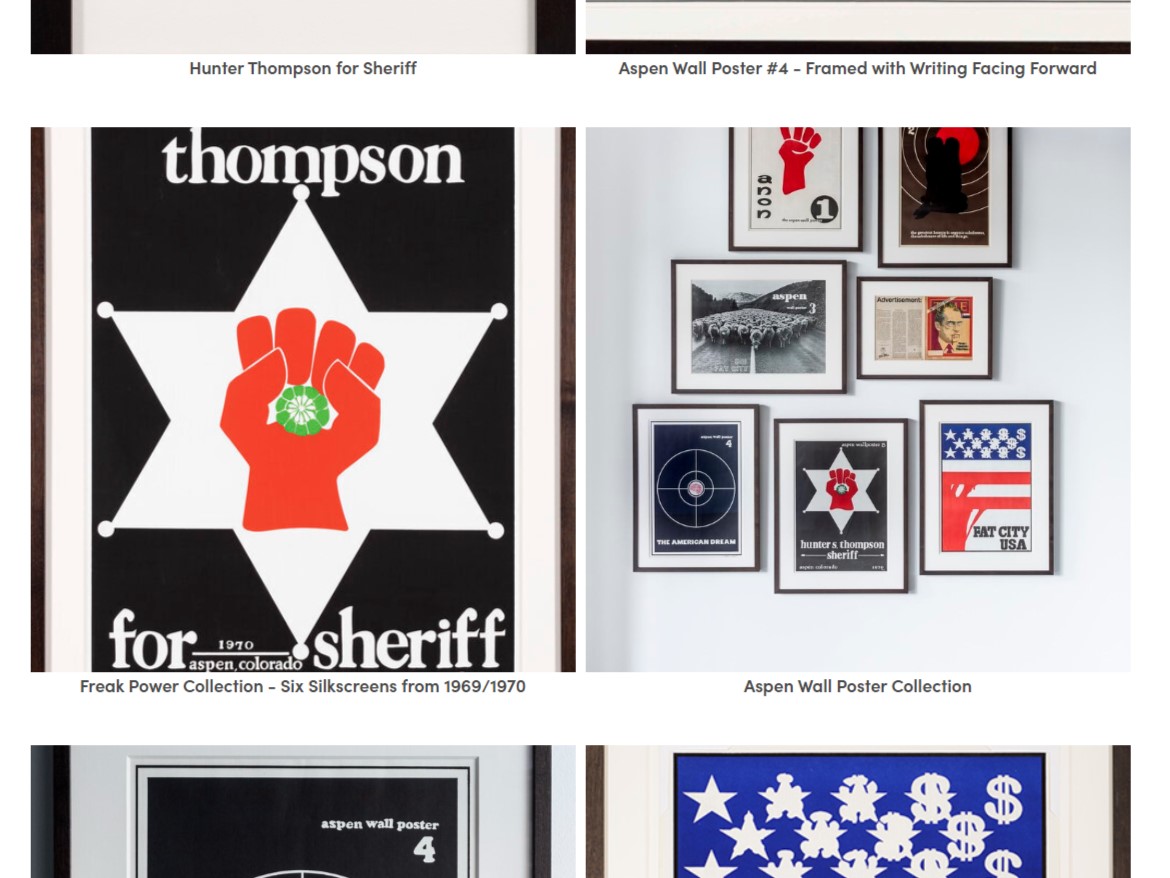

As part of his campaign for Sheriff, Thompson and local Aspen artist Tom Benton had conceived of the Aspen Wallposters, featuring graphics by Benton on one side and Thompson’s campaign writing on the other. The most instantly recognizable wallposter was the now iconic Wallposter No. 5, the Thompson for Sheriff election poster featuring a red double-thumbed fist clutching a green peyote button, set in the middle of a white sheriff’s badge on a black background. The two thumbed fist stood for the Freak Power platform, the peyote button representing the wider drug counterculture. Other notable entries included a censored wallposter that depicted Nixon with blood running from his mouth and swastika eyeballs, and one depicting a highway covered in sheep entitled “Ski Fat City”.

Coinciding with the wallposter series, Thompson had launched his tentative platform for sheriff in the October 1970 issue of Rolling Stone, as part of his debut piece for the magazine entitled “Freak Power in the Rockies — The Battle of Aspen.” Here he proposed ripping up the streets of Aspen with jackhammers, changing the name ‘Aspen’ by public referendum to ‘Fat City’ so as to “prevent greed heads, land-rapers and other human jackals from capitalizing on the name ‘Aspen,’” promised that his first act as Sheriff would be to set up a bastinado platform and a set of stocks on the courthouse lawn to punish dishonest dope dealers, declared that it would be “the general philosophy of the Sheriff’s office that no drug worth taking should be sold for money” and that “the Sheriff and his deputies should never be armed in public.”

To allay any fears concerning his own drug consumption as Sheriff, Reverend Thompson also promised, in the course of his campaign, not to consume mescaline while on duty.

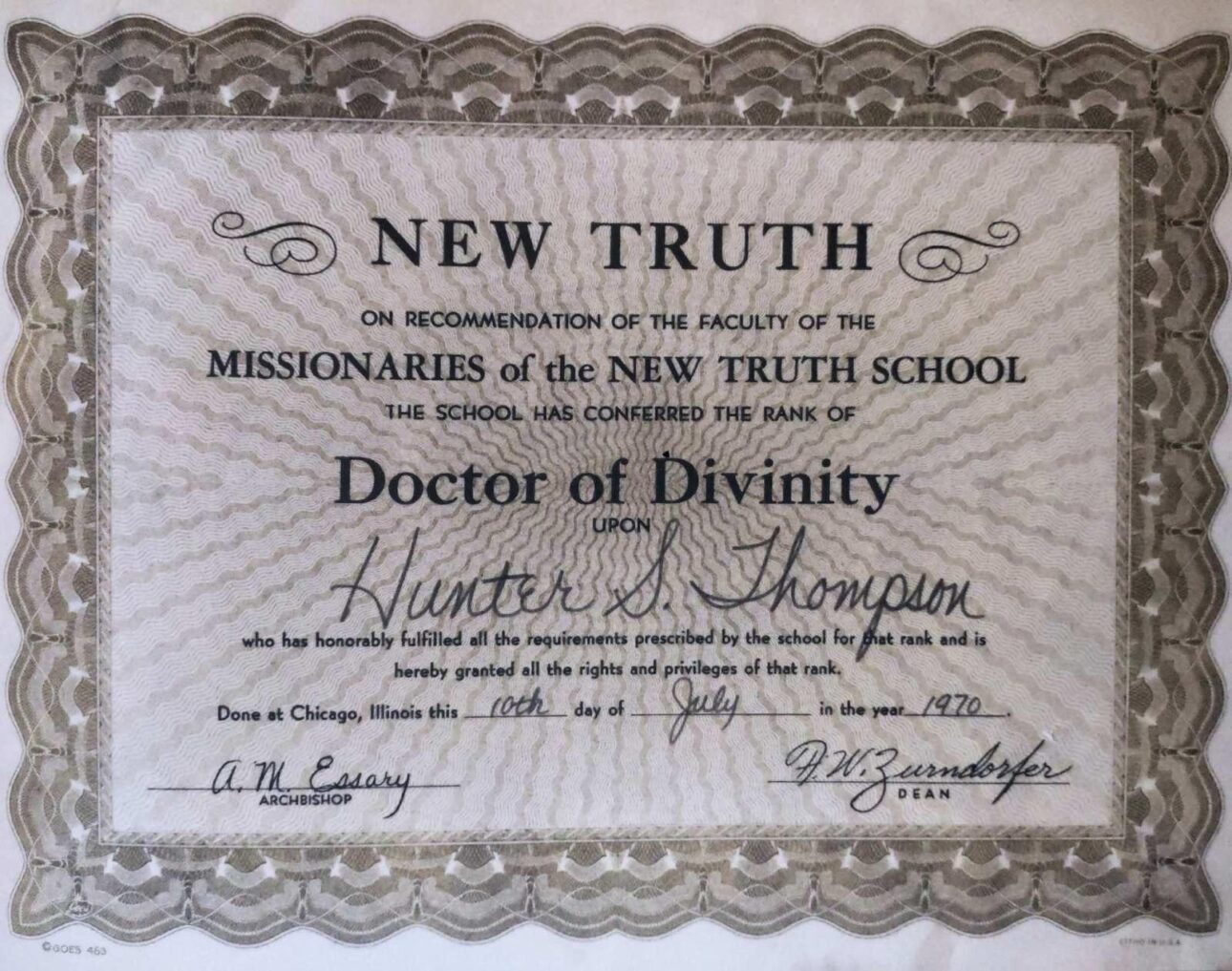

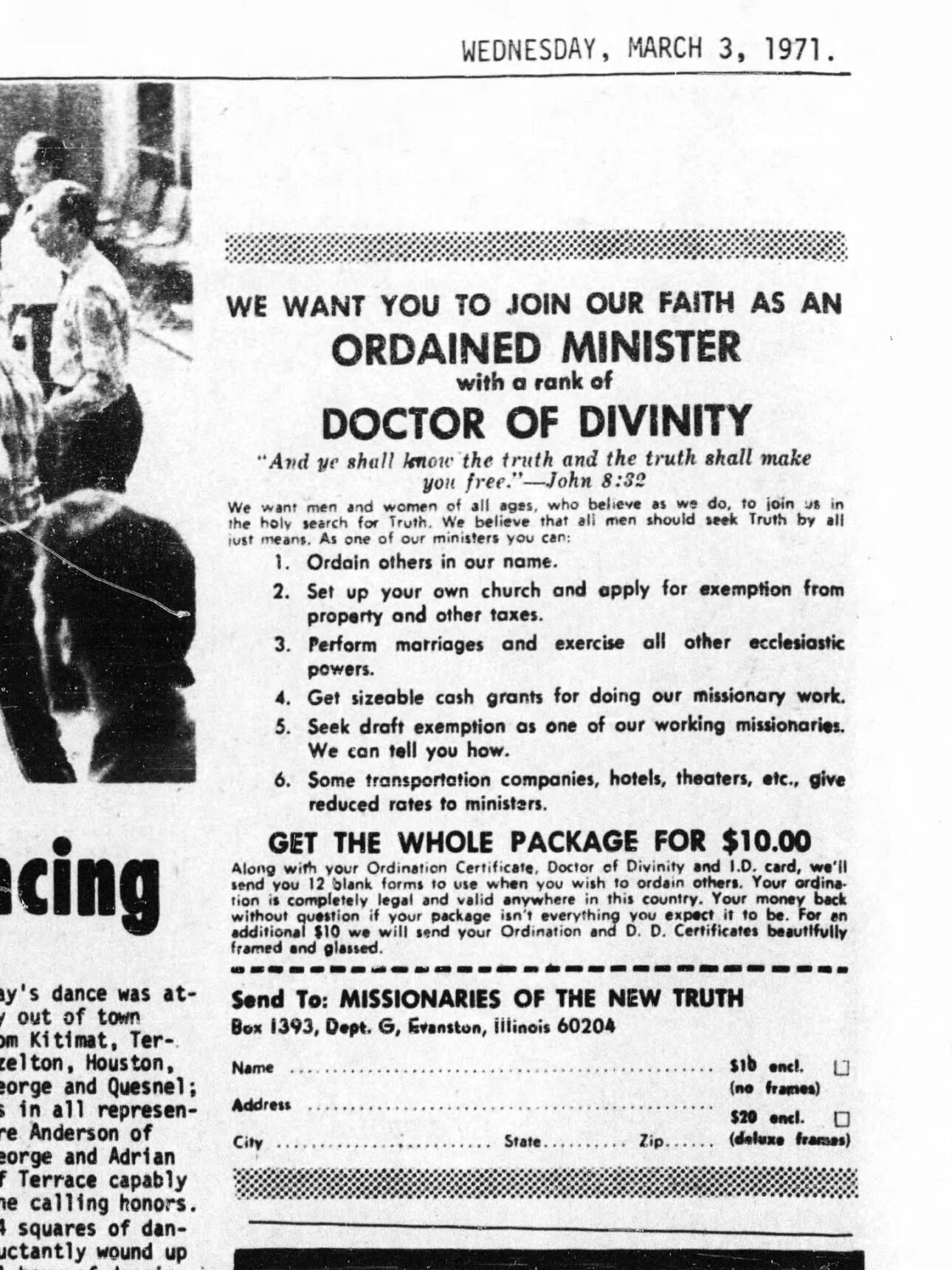

The Rolling Stone piece is notable in that it also marks the first major article by Thompson in which he had adopted his doctor moniker. As to what exactly Thompson’s doctorate was in, that was a question to which the answer varied, depending on the situation. Years after his Sheriff campaign, when questioned about his credentials by David Letterman, an amused Thompson stated that his doctorate was in “journalism, chemotherapy and divinity.” It was an answer that was at least partly true. The Good Doctor was indeed a man of the cloth, having received his doctorate from the Missionaries of the New Truth, a church operating out of Chicago.

Thompson had been officially conferred as a Doctor of Divinity by the church on July 10th, 1970 after a suggestion of his Wallposter collaborator and friend, Tom Benton, who later explained:

At some point somebody had bought me a subscription to the Los Angeles Free Press, and every week I’d get it, and the back page always had this ad — “Get your doctorate of divinity degree for $10” — so I went to Hunter and said, “Look man. Wouldn’t it be nice if we called ourselves “Dr. Thompson” and “Dr. Benton?” […] We got them, and Hunter said, “This is great, because you get cut rates on hotels. And you know, it always sounds good in an airport when you hear ‘Paging Dr. Thompson.’”

Tom Benton, quoted in “Gonzo: the Life of Hunter S. Thompson” by Corey Seymour and Jann S. Wenner

Of course, it didn’t take long for Thompson to exercise his new ecclesiastical powers; he officiated a wedding with somewhat mixed results, with Thompson scaring the living daylights out of the bride-to-be courtesy of an electrotherapy device that he waved in her face, resulting in an electrical current arcing across from the gadget, hitting her on the nose. Afterwards he made a deal with Benton: “You do all the weddings and I’ll do all the funerals.”

Established in 1969 under the auspices of Frederick W. Zurndorfer and David A. Muncaster of Chicago, The Missionaries of the New Truth had first come to public attention in early 1970 when various reporters had profiled the church, having successfully purchased mail order doctorates. The articles focused mainly on the advantages of membership that were pushed heavily in the Church’s advertising, from tax benefits to discounts in hotels, theatres and transportation companies for members of the clergy. Another major claimed selling point was that ordained ministers could obtain privileges and exemptions from local, state, and federal governments and the armed forces, specifically the draft.

Writing for the Sun-Tattler in Hollywood, Florida, Arthur Rosett reported that according to B.L. David, then Hollywood city attorney — “There is nothing in the legal code of the state of Florida that prevents you from solemnizing marriages. After all, you are an ordained minister from a church recognised and incorporated under the laws of the state of Illinois. As for your other privileges, it sounds water-tight Reverend.”

Ecclesiastical figures were not so enthused by the Missionaries of the New Truth however, with Reverend Roy B. Connor D.D. of the First Presbyterian Church of Hollywood offering his view of the newfound Church – “I am aware that this goes on. My personal feeling is that it is of more interest and profitable to an individual than it is to the people of a community. However, it is perfectly legal and there is nothing we can do about it.”

As public interest in the Church grew, so too did opposition to its existence. In a June 1970 profile on the group in the Vermont press, Judge J. William O’ Brien was vehement in his condemnation: “There’s no question about it in my mind. There are some people behind this sort of thing who are out to destroy organized religion by setting up these cults. And this sort of thing will work to the detriment of sincere groups who want to start a different religion and have something to offer.” Scrutiny also began to fall upon the figures behind the Church itself. Though Frederich W. Zurndorfer was Dean of the Church, whose signature appeared on the issued doctoral certificates, alongside Archbishop A.M. Essary, the central figurehead and voice of the church was Archbishop David A. Muncaster. It was Muncaster who authored the official creed of the church, in which he outlined the central tenets by which members agreed to abide.

“We believe in man as a seeker of Truth,” proclaims the creed. “We believe the nobility of man lies in the seeking of these truths. If a man is to live a meaningful, happy life, he must seek the truth.” As the Rev. George Lambert D.D., a fellow Truther, observed in his article for the Burlington Free Press, — “when it comes to procedure on seeking the Truth and just what constitutes ‘The Truth,’ Archbishop Muncaster begins to hedge.”

“We believe that certain Truths all differ for each man, as each man is different […] for this reason we place no restrictions on man’s search for Truth except that he follow his best convictions with honesty and integrity. We thus exhort all our members to seek the Truth by all just means in any place and in any way they see fit.” Muncaster closed out the Creed with a simple declaration: “We pledge to keep our faith as free as possible from encumbering dogma and stultifying moral and social strictures.”

By the fall of 1970, though, the Church and Muncaster were facing more serious scrutiny beyond that of journalistic enquiries when they were officially investigated by the Not-for-Profit Corporation Study Commission of the Illinois state legislature. The Missionaries of the New Truth had come to the attention of the commission in relation to one of their members — one Lance D. Broadhead, Doctor of Divinity and licensed, ordained minister. The D. was for dog. Lance Broadhead was a full-grown collie. It was unclear if the Rev. Broadhead had officiated any weddings, or indeed funerals, in his capacity as minister. His owner, a shepherd, that lived in La Crosse, Wisconsin, had obtained his dogs’ doctorate by the usual $10 mail order check routine.

Muncaster and his attorney, David R. McKenzie, defended the church in front of the commission, with Muncaster stating that the church was set up “to establish schools for religious training, and to establish churches and to perform all necessary activities for the propagation of our faith.” Muncaster also revealed the enormous success of the church in the scope of one year, claiming to have ordained 7,000 ministers throughout the world and that the church had a treasury of $15,000. In his statement to the commission, Muncaster also asserted that any person “who is honestly searching for the truth” can become an ordained minister for $10.

Responding to Muncaster and the ordained collie, the Rev. Lance D. (for dog) Broadhead, State Rep. John E. Friedland said – “Well, I hope Lance is sincere in his search for the Truth.”

Meanwhile, in Aspen, Thompson’s Campaign for Sheriff had to confront a bitter defeat to the Republican incumbent; though Thompson received 1065 votes and won two districts in the city, he lost the county vote by a considerable margin. Ultimately, he won 44 percent of the overall vote and lost by 400 votes. In their final wall poster collaboration, Dr. Thompson and Dr. Benton offered the following account of Thompson’s concession speech, one with a humorous nod to his newfound religious standing:

“In his final, election-night speech for the national press and TV, the candidate lost control of himself and had to be restrained: “This is my last press conference!” he shouted. “You won’t have Hunter Thompson to kick around anymore, you pigfuckers!” He then rushed out of the room to confer with his personal swami, who later told reporters that Dr. Thompson had decided to “depart this country in the spring” and take up permanent residence at a luxurious ashram on the Bay of Bengal.”

In reality, Thompson’s actual concession speech offered an altogether more sobering assessment of the election outcome and what it meant for Aspen and America at large – “I think I unfortunately proved what I set out to prove — which was more a political point than a local election […] that the American dream really is fucked […] and we made a mistake in thinking that the town was ready for an honest political campaign.”

While Thompson retreated to Owl Farm, his fortified compound in Woody Creek, Colorado, to contemplate the ramifications of his doomed political campaign, over in Chicago, the Missionaries of the New Truth faced their own serious problem.

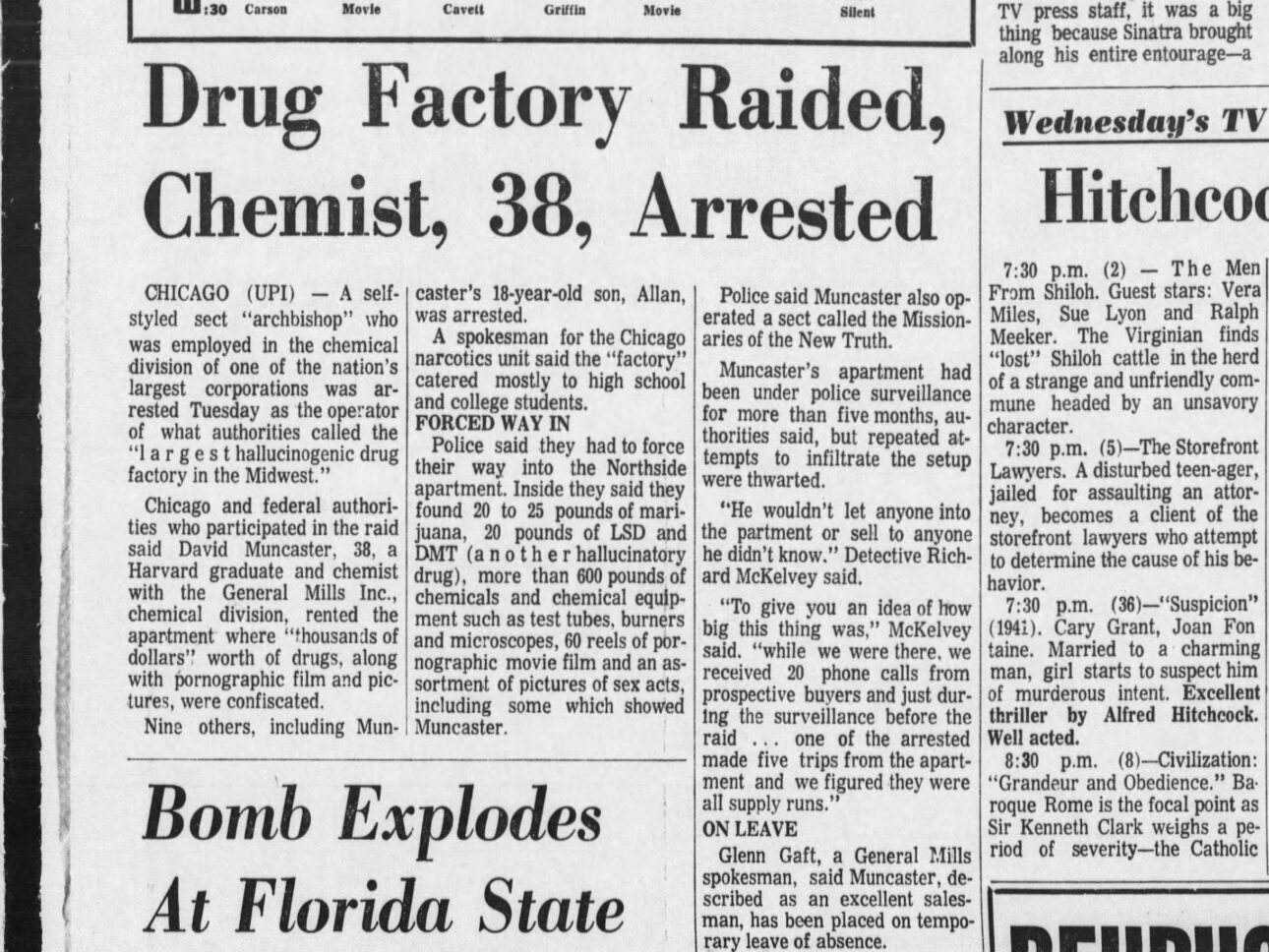

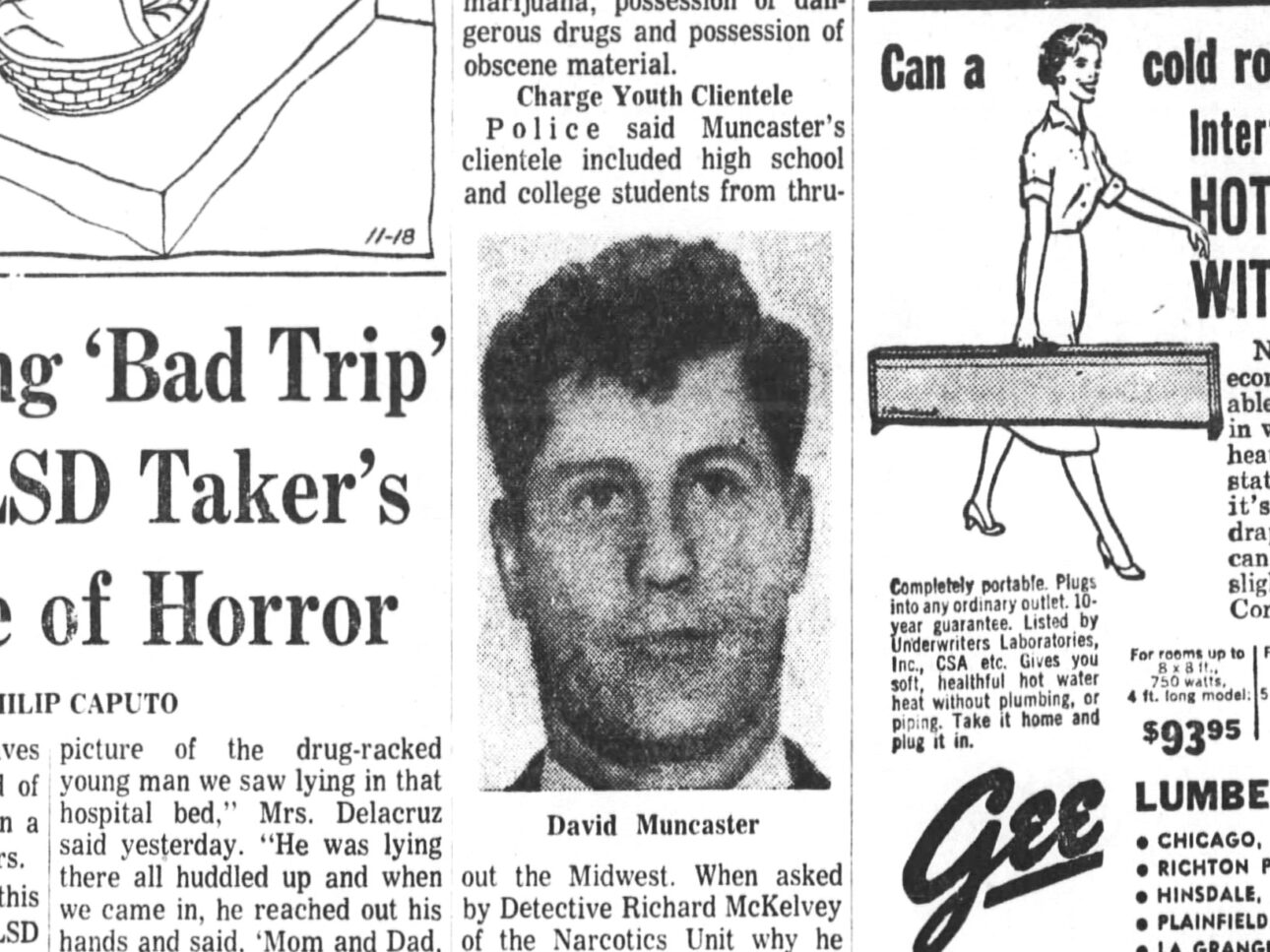

On November 17th 1970, Archbishop David A. Muncaster was arrested as the operator of what authorities called “the largest hallucinogenic drug factory in the Midwest.” According to the Chicago Tribune, police said they confiscated “20 to 25 pounds of marijuana, 20 pounds of LSD and DMT, more than 600 pounds of chemicals and chemical equipment, 60 reels of pornographic movie film and a variety of photos depicting sexual acts, including several of Muncaster.” In total, 10 people had been arrested, including Muncaster’s 18-year-old son Allan, who was a chemistry major at Northwestern University, and another Missionaries of the New Truth Archbishop, A.M. “Toni” Essary, who had co-signed Hunter S. Thompson’s doctoral certificate.

Federal authorities and the Chicago Police Narcotics Unit raided Muncaster’s apartment after it had been under surveillance for more than five months, with police stating it was the headquarters for Muncaster’s drug factory and the Missionaries of the New Truth. “To give you an idea of how big this thing was, while we were there, we received 20 phone calls from prospective buyers,” said Detective Richard McKelvey of the Narcotics Unit.

According to newspaper reports, Muncaster, a Harvard University graduate, was employed as a senior sales representative for the chemical sales division of General Mills, one of the nation’s largest corporations, whose spokesman described Muncaster as an “excellent salesman.” Muncaster’s clients had been high school and college students from across the Mid-West. Police charged Muncaster with possession of marijuana, possession of dangerous drugs, and possession of obscene material. Detective McKelvey said that Archbishop Muncaster had been charged with marijuana possession previously in 1965, but was not convicted. When he pressed Muncaster as to his motivation for dealing drugs, the Good Archbishop replied: “Just for kicks.”

By January of 1971, the Missionaries of the New Truth had also come to the attention of Illinois Attorney General William Scott, who sought to shut down the church for illegally soliciting funds as a nonprofit organization for fraudulent purposes. Scott filed a complaint in the State Circuit Court seeking to dissolve the church’s state charter and freeze all its bank accounts. Ironically, Attorney General Scott himself was later convicted of tax fraud and sentenced to a year in prison.

While Muncaster and the Church dealt with their legal woes, another of their ordained ministers had also run into a legal quandary, with the Springfield News Leader in Missouri reporting that the Buchanan County Draft board had rejected a Ministerial Deferment request from a Truther, which had been one of the Church’s central selling points in their brochure, advising that one could qualify for a draft exemption as a “working missionary.” The paper reported that draft regulations stipulated that exemptions were only offered to affiliates of a “recognized church or religious body.” The Truther was subsequently classified by the Draft board as 1-A: available for military service. Hunter S. Thompson in the meantime, along with his inimitable Chicano attorney, Oscar Zeta Acosta, found himself locked into an even more bizarre and subversive trip than his Freak Power exploits, as he sought to write a new story after his debut piece for Rolling Stone. Following his failed sheriff campaign, Thompson had taken up writing about the Chicano Movement, no doubt under the influence of Oscar Zeta Acosta, who was an activist attorney in the Chicano barrio of East Los Angeles and who, like Thompson, had also run for sheriff, contesting the Los Angeles County race in 1970 and receiving over 100,000 votes.

If Thompson had been an unconventional candidate for sheriff, Oscar Acosta, with the nom de plume ‘the Brown Buffalo,’ was even more so. As a lawyer, his passionate defense of his clients often spilled over from sheer brilliance to outright insanity. Thompson himself had one night witnessed Acosta pour ten gallons of gasoline on the front lawn of a judge’s house in Santa Monica and then promptly set the whole yard ablaze, as a means to communicate with the judge, who had been somewhat difficult to deal with in court. Unfazed at being recognised, Acosta stood his ground in front of the house and “howled through the flames at a face peering out from a shattered upstairs window.”

And if Thompson was a Doctor of Divinity from the Missionaries of the New Truth, Oscar one-upped him by having been a Baptist missionary at a leper colony in Panama before becoming a lawyer. As the fire roared into the sky in front of the house, Acosta delivered an impromptu sermon on justice straight from the Bible. As Thompson noted, “the Lawn of Fire was Oscar’s answer to the Ku Klux Klan’s burning cross, and he derived the same demonic satisfaction from doing it.”

Truth and Justice were common causes for Thompson and Acosta, no matter how idiosyncratic their manner of pursuing them, and it was this motivational angle that shaped Thompson’s Chicano story following the high-profile death of journalist and activist Ruben Salazar, who was killed during an anti-war demonstration in East Los Angeles in August of 1970. Salazar had been writing about the Chicano movement for the Los Angeles Times and was particularly critical of the L.A.P.D. While covering the National Chicano Moratorium March in his role as news director for KMEX television station, a confrontation with the police devolved into a full-blown riot. Salazar was sheltering from the unfolding chaos in a café, when a sheriff’s deputy shot a high-powered tear gas canister through the front door, striking Salazar in the head and killing him.

It was precisely the angle that Thompson had been looking for in writing about the Chicano movement, allowing him to address their wider concerns through the prism of a police department taking murderous revenge on a journalist that had stoked their ire for simply doing his job. Thompson’s ensuing article, “Strange Rumblings in Aztlan” was published by Rolling Stone in April 1970 and was a damning indictment of the L.A.P.D. and the media coverage of Salazar’s death. Though restrained by Thompson’s standards in delivery and tone, it proved to be the launchpad for his next project and one that catapulted Thompson into literary infamy — Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

While covering the Salazar piece in East Los Angeles, Thompson had accepted another assignment from Sports Illustrated to cover the Mint 400 Off-Road motorcycle and dune buggy race in the desert outside Vegas, which was sponsored by Del Webb’s Mint Hotel and Casino. Thompson had little interest in the race itself but saw it as a useful excuse to get himself and Acosta out of the pressure cooker that was East Los Angeles following Salazar’s death. In the East L.A. barrio, Thompson was viewed with suspicion and, though Oscar Acosta was helping him to understand the dynamic between the minority community and the powers that be, Thompson found himself surrounded by Chicano militants, some of whom were Acosta’s bodyguards and some who made it clear they would stomp him without hesitation. It was not exactly a conducive environment for a gringo journalist to be asking pointed and sensitive questions. Thompson reasoned that in taking a road trip to Vegas, they could relax and talk freely. And so, on March 20th 1971, Thompson and Acosta hired a Chevrolet convertible, christened the Great Red Shark, and drove from Los Angeles to Las Vegas, the first of two trips to Sin City that would form the basis of Thompson’s infamous tale.

That first weekend in Nevada, Thompson and Acosta careened around Vegas fueled by alcohol, Dexedrine, and a large quantity of marijuana. Though not quite the smorgasbord of pharmaceuticals and psychedelics that Raoul Duke famously catalogues, it was enough to get them into serious trouble if caught, particularly the marijuana under Nevada law. They stayed out all night and the next morning, Sunday March 21st, Thompson drove to the Mint Gun Club to cover the off-road race, which largely turned out to be the equivalent of viewing a motor-charged dust storm. That evening, Acosta flew back to Los Angeles in order to be in court first thing Monday morning, leaving behind with Thompson the marijuana and a loaded .357 Magnum. It was enough to send Thompson completely over the edge; he was seized by paranoia and panic at the prospect of being caught with either the drugs or the gun, or indeed both. He also had the sudden realization that he couldn’t afford to pay the hotel bill, having racked up several hundred dollars on the room service tab alone. So naturally, the Good Doctor decided to burn the hotel and let Sports Illustrated, who had booked the room, deal with the bill.

Planning to flee the hotel at dawn, Thompson spent the remainder of the night holed up in his hotel room scrawling notes on the Mint Hotel stationary in a paranoid drink and drug fueled frenzy. These notes formed the basis for the first draft of Part 1 of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas with Thompson completing a revised draft at a motel in Pasadena, in between working on his Ruben Salazar story. Later, when Sports Illustrated “aggressively rejected” Thompson’s 15,000-word submission, having originally requested a much smaller article on the Mint 400 race, Thompson sent them a letter in which he wrote: “Your call was the key to a massive freak-out. The result is still up in the air, and still climbing. When you see the final fireball, remember that it was all your fault.”

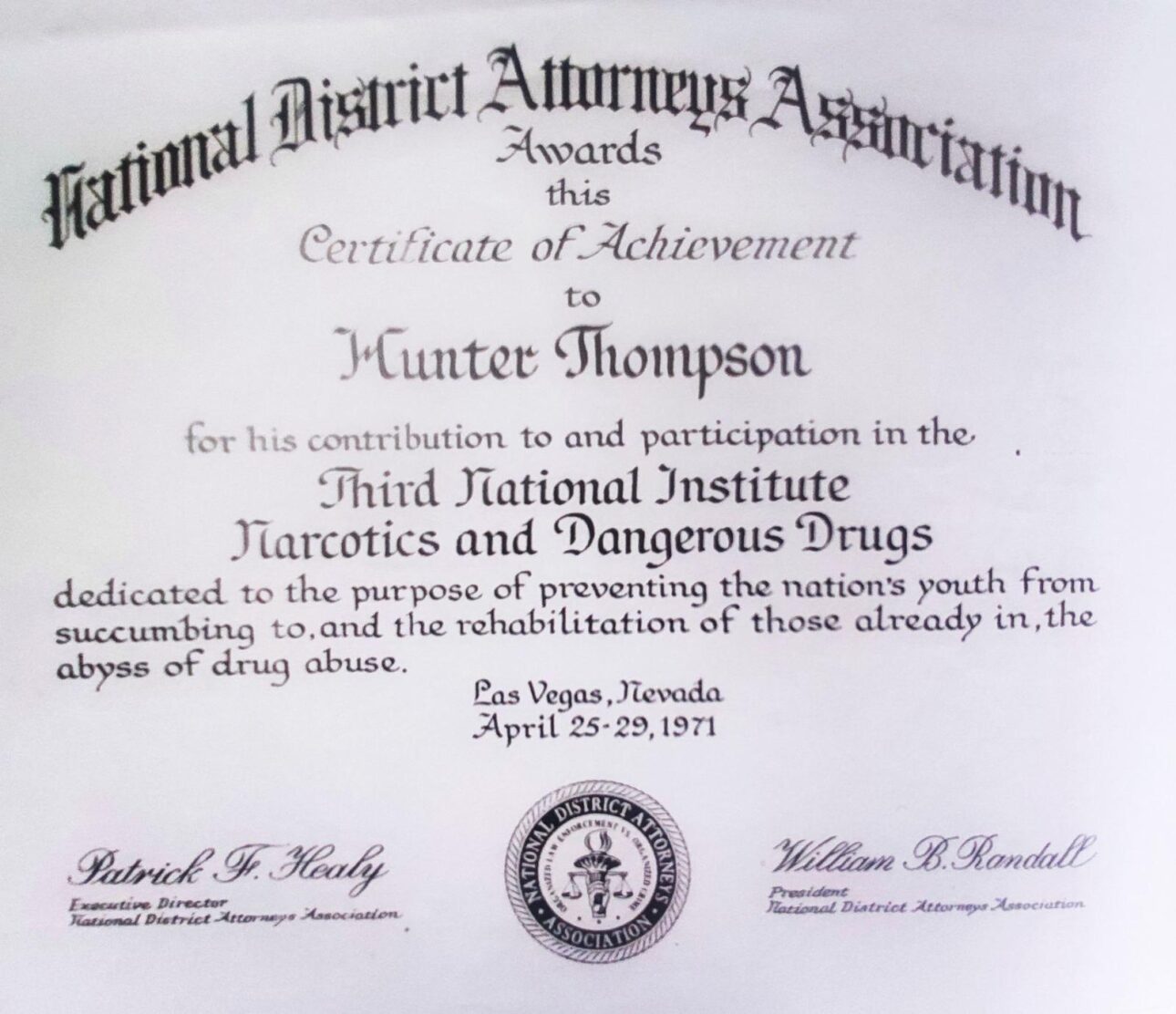

Fortunately for Thompson, his efforts at crafting his Vegas trip into the much longer story of the exploits of Raoul Duke and his attorney, Dr. Gonzo, had not entirely gone to waste. David Felton, his editor for the Ruben Salazar story at Rolling Stone, pushed Thompson to keep writing and developing the story. Thompson however, initially struggled to expand on his original draft, now that he was no longer in Vegas and, effectively, away from the scene of the crime. Felton, to his credit, offered up the perfect solution. He was aware of an upcoming event in Vegas that might just provide Thompson with the necessary material needed for his story. The National District Attorneys Association were sponsoring a four-day conference, the Third National Institute on Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs. It was perfect.

Thompson and Acosta flew to Las Vegas to attend the event, which was scheduled between April 25th – 29th at the Dunes Hotel. On arrival in Vegas, they hired a white Cadillac convertible and checked in at the Flamingo Hotel & Casino. From the onset, this trip was going to be far different to the Mint 400 gig, with Thompson, in the guise of Raoul Duke, later observing: “But this time our very presence would be an outrage. We would be attending the conference under false pretenses and dealing, from the start, with a crowd that was convened for the stated purpose of putting people like us in jail. We were the Menace – not in disguise, but stone-obvious drug abusers, with a flagrantly cranked-up act that we intended to push all the way to the limit […] not to prove any final, sociological point, and not even as a conscious mockery: It was mainly a matter of life-style, a sense of obligation and even duty. If the Pigs were gathering in Vegas for a top-level Drug Conference, we felt the drug culture should be represented.”

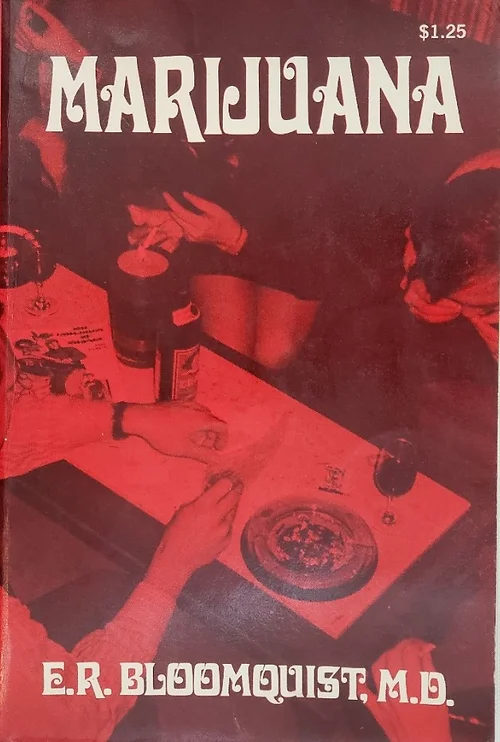

The keynote speaker at the conference that week was E.R. Bloomquist, MD, who had authored a book titled Marijuana, that proclaimed to “tell it like it is.” Bloomquist was an Associate Clinical Professor of Surgery (Anesthesiology) at the University of Southern California School of Medicine and was a well respected academic expert that served as a consultant for a variety of government agencies and forums. As Bloomquist delivered his address to the gathered crowd of almost 1500, Thompson and Acosta could hardly believe what they were hearing:

“We must come to terms with the Drug Culture in this country!…country…country…” These echoes drifted back to the rear in confused waves. “The reefer butt is called a ‘roach’ because it resembles a cockroach…cockroach…cockroach…” … “What the fuck are these people talking about?” my attorney whispered. “You’d have to be crazy on acid to think a joint looked like a goddamn cockroach!”

Thompson, in particular, had nothing but contempt for what Bloomquist was selling, having made the laws around marijuana one of the central platforms in his campaign for sheriff. Thompson had rejected the idea that possession of marijuana should be a felony for first-time offenders, was in favor of legalization, and viewed drug abuse as a community issue and one that should be tackled through treatment instead of imprisonment. In Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, he liberally quoted from Bloomquist’s book:

“Dr. Bloomquist’s book is a compendium of state bullshit. On page 49 he explains, the “four states of being” in the cannabis society: “Cool, Groovy, Hip & Square” – in that descending order. “The square is seldom if ever cool,” says Bloomquist. “He is ‘not with it,’ that is, he doesn’t know ‘what’s happening.’ But if he manages to figure it out, he moves up a notch to ‘hip.’ And if he can bring himself to approve of what’s happening, he becomes ‘groovy.’ And after that, with much luck and perseverance, he can rise to the rank of ‘cool.’”

Reverend Dr. Thompson ruminating on E.R. Bloomquist M.D.’s sociological analysis of weed culture.

Thompson had intended to satirize the entire event from the onset of his trip, but he quickly realized that what Acosta and himself were witnessing was so absurd and out of touch, that lampooning it wasn’t even necessary. That aside, his depiction of the conference in the pages of Rolling Stone still allowed for his trademark blurring of fact and fiction with his added flair for subversive humor. As Raoul Duke, Thompson claimed to have registered for the conference as “a private investigator from L.A. – which was true, in a sense; and my attorney’s name-tag identified him as an expert in “Criminal Drug Analysis.” Which was also true, in a sense.” Indeed, Thompson actually received a certificate of achievement at the conference, for his contribution to and participation in the Third National Institute Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs dedicated to the purpose of preventing the nation’s youth from succumbing to, and the rehabilitation of those already in, the abyss of drug abuse.

It wasn’t lost on either Thompson or Acosta that, while they sat in the crowd of 1500 listening to Dr. Bloomquist’s warnings, they had once more brought a sizable cache of Benzedrine, Dexedrine, and marijuana with them to Las Vegas that week. Unlike the book however, they had no psychedelics, a fact that Thompson laments in the audio recordings he made in Vegas, released in 2008 as The Gonzo Tapes. The recordings are an astonishing artifact from that trip, revealing the many conversations between Thompson, Acosta, and the various characters they met in Las Vegas, which made it word for word into Thompson’s ensuing story. The tapes reveal Thompson lamenting that he didn’t bring any mescaline with him and, later, contemplating getting his hands on ether. At one point, as Thompson and Acosta drive through the streets of Vegas, Brewer and Shipley’s One Toke Over the Line can be heard playing on the car radio, prompting Thompson to exclaim – “Here we go, this is a song!” – at which point he cranks the volume. Thompson and Acosta appear to have spent much of their time in Vegas driving around the city, enquiring with random people if they knew where the American Dream could be found. One of these encounters, at a Taco Stand, was subsequently transcribed word for word as chapter 9 of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: Breakdown on Paradise Blvd. As Acosta later observes on the recordings — “Whilst taking a piss there it struck me what’s going on here, with us, this assignment. Anybody that is in search of the American Dream needs a lawyer, a doctor, and a bodyguard, because there is no way to look for it, without that sort of guidance.”

Eventually, after several days of heavy drinking and drug use, Acosta decided to return to Los Angeles, leaving Thompson once more to contemplate the week’s events alone, this time at the Tropicana hotel. Much like the last time, he was gripped by paranoia as he made notes, before flying back to Colorado the next day. His arrival in Denver marked the end of his trip and is also where he wraps up the subsequent story, wherein Raoul Duke notably invokes his ministerial credentials:

“I jerked out my wallet and let her see the police badge while I flipped through the deck until I located my Ecclesiastical Discount Card – which identifies me as a Doctor of Divinity, a certified Minister of the Church of the New Truth … I paid without quibbling about the ecclesiastical discount. Then I opened the box and cracked one under my nose immediately, while she watched … I was just another fucked-up cleric with a bad heart … I took another big hit off the amyl, and by the time I got to the bar my heart was full of joy. I felt like a monster reincarnation of Horatio Alger … a Man on the Move, and just sick enough to be totally confident.”

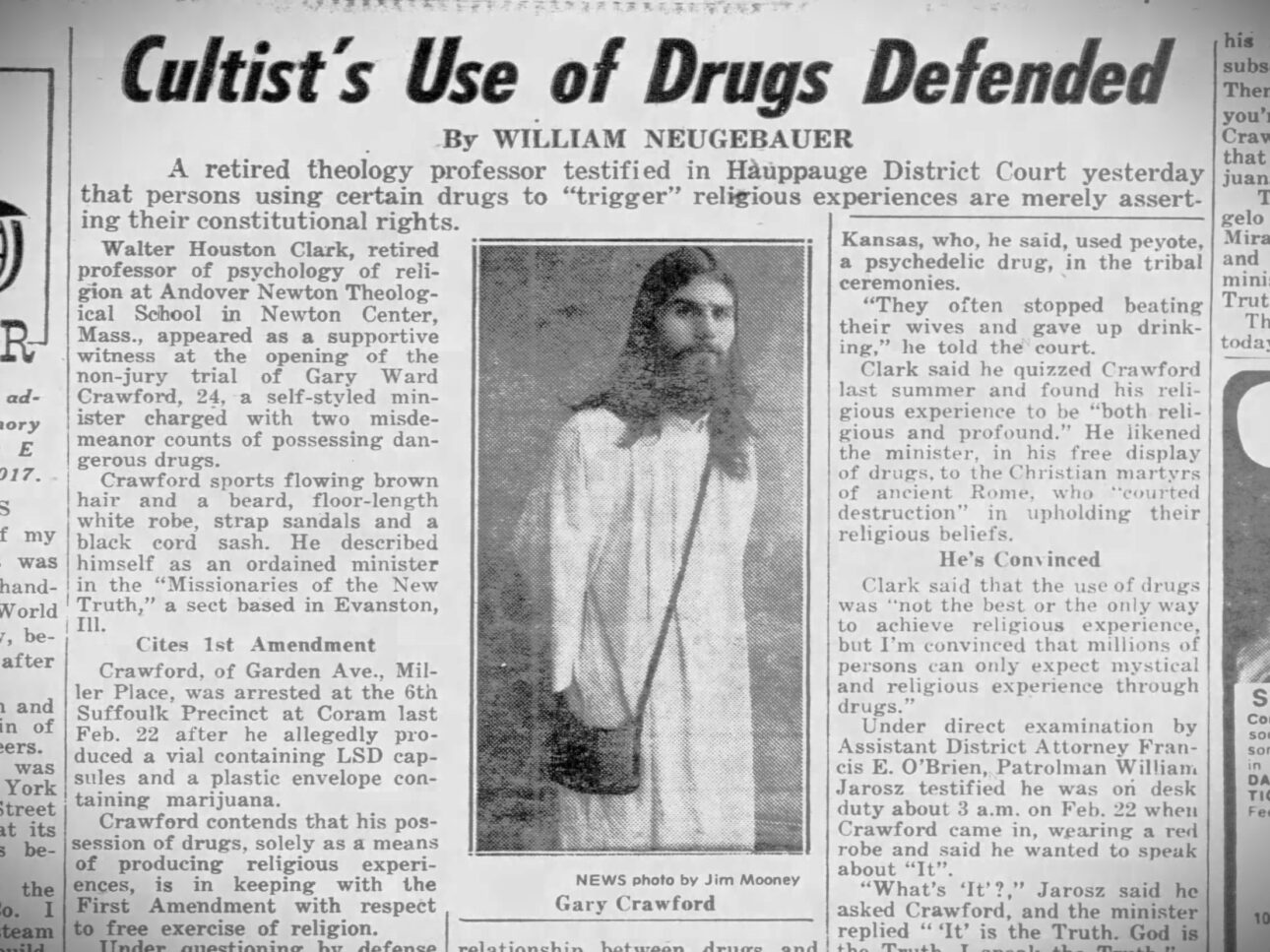

Not all Truthers enjoyed the same benefits as the Rev. Dr. Thompson however, with one of the faithful, 24-year-old Rev. Gary Ward Crawford, sentenced to nine months in jail on April 5th, 1972, after being convicted for possession of LSD and marijuana which he had claimed were used to trigger religious experiences. With his long hair and beard, Crawford appeared to be invoking Jesus in his court appearance, aided by his long flowing white robe, brocaded sash and open sandals. Prior to his ordination as a minister by the Missionaries of the New Truth, Crawford told the court that he had used LSD about 30 to 40 times and marijuana about 500 times. He had been arrested after he went to a police station and approached a desk officer and produced a vial of LSD and an envelope of marijuana. Crawford informed the court that he had visited the station in order to discuss the contradiction in laws relating to drugs and religious observance. Speaking of his mystical experiences, Crawford testified that it involved “temporarily losing one’s awareness” and that he first discovered this in February 1969:

“My identification with Gary Crawford became suspended. I myself was not Gary Crawford. I was everything and everywhere. I was without form, without limit, having no beginning and no end.”

According to the New York Daily News the Rev. Crawford had put forth the argument that his arrest had violated his constitutional rights under the first amendment. Rev. Crawford cited a 1965 California Supreme Court ruling that allowed the Navajo Nation to use peyote for religious ceremonies. In sentencing Crawford, Judge Angelo Mauceri wrote there was no evidence indicating that the Missionaries of the New Truth used drugs in ceremonies or that drugs were “an intrinsic part of the dogma of his (Crawford’s) church.”” It is unclear if Judge Mauceri had been made aware of the activities of the Church’s Archbishop, in Chicago, when sentencing Rev. Crawford.

Despite the legal woes of the Church and its entanglement with federal authorities, it appears the Good Archbishop Muncaster was as devoted as ever to his mission, at least in terms of getting his kicks, if not the Truth. On April 26th, 1973, two men were arrested in Springfield, Tennessee after federal and state drug agents raided what was described as “a clandestine drug laboratory in the basement of a farmhouse […] the agents said they seized flasks, vials and other lab equipment and chemicals needed to manufacture amphetamines and methamphetamines.” George Baral, 27 and Michael Hamilton, 24, both from Chicago, were charged with conspiracy to manufacture controlled substances. A third man from Chicago, David Muncaster, was also charged but his whereabouts were unknown to the authorities.

According to the Tennessean, “the raid ended a six months’ surveillance by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, beginning when Chicago BNDD agents observed Muncaster and a woman, Toni Essary, loading cartons into a U-Haul trailer.” The trailer was subsequently transported from Illinois to a storage company in Nashville. Muncaster told the storage firm that he was setting up a branch of the Bryan Chemical Co. of Chicago, near Nashville. An affidavit that accompanied the search warrant for the farmhouse stated that Muncaster had given the address of a law firm in Nashville as the location of his branch of the Bryan Chemical Co. and that Muncaster had used the name “Arthur Gilbert” in his dealings with the storage company in Nashville. His accomplice, Toni Essary, was, of course, A.M. Essary, fellow Archbishop of the Missionaries of the New Truth, who had previously been arrested alongside Muncaster in relation to the 1970 drug bust in Chicago. Following the collapse of the trial against Hamilton and Baral in 1974, Muncaster was described as “a fugitive who has never been indicted.” According to authorities, Muncaster was believed to be hiding out in Florida.

For Dr. Hunter S. Thompson, 1974 was something of an end of a watershed moment. His arch nemesis, Richard Nixon, had fled the White House like a diseased cur after the Watergate scandal and in his disappearance from the political scene, Thompson lost perhaps his greatest muse. In October of 1974, Thompson also learned of the disappearance of his attorney and friend Oscar Zeta Acosta after he received a letter from Annie Acosta, sister of Oscar, appealing for help after her brother mysteriously disappeared in the spring of that year:

“Two ugly rumors – he was shot and on a yacht doing a bit of smuggling! Well Hunter – I am desperate and seriously fear for his life. He has been sought after by too many ugly gabachos & I dare them to think it may have ended, if you know what I mean! Oscar always thought the world of you – hopefully it works both ways. Could you possibly think of something that could be done – I have written & phoned just about everyone here in California that he may possibly have had contact with…nothing.”

Oscar Zeta Acosta was never seen, or heard from, again. Thompson appealed to Jann Wenner of Rolling Stone for help, writing — “I think Oscar’s ominous disappearance is a story we have an obligation to do.” However, it wasn’t until 1977, that Rolling Stone finally covered Oscar’s disappearance, when they published Thompson’s requiem for his vanished attorney, The Banshee Screams for Buffalo Meat. Here Thompson addressed the speculation that had built up in the intervening years regarding Oscar’s fate:

“Ever since his alleged death/disappearance in 1973, ’74 or even 1975, he’s turned up all over the world—selling guns in Addis Ababa, buying orphans in Cambodia, smoking weed with Henry Kissinger in Acapulco, hanging around the airport bar in Lima with two or three overstuffed Pan Am flight bags on both shoulders or hunched impatiently on the steering wheel of a silver 450 Mercedes in the “Nothing to Declare” lane on the Mexican side of the U.S. Customs checkpoint between San Diego and Tijuana.”

Acosta’s death was another serious blow to Thompson, losing not only a friend but also another big influence and source of inspiration. It is unsurprising that in writing of his loss that Thompson invoked a comparison with his other muse:

“And now—as an almost perfect tribute to every icepick ever wielded in the name of Justice—I want to enter into the permanent record, at this point, as a strange but unchallenged fact that Oscar Z. Acosta was never disbarred from the practice of law in the state of California—and ex-President Richard Nixon was.” In 2018, Tangerine Press published a magnificent reissue of Oscar Zeta Acosta’s The Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo with an afterword by his son Marco Acosta, in which he offered further insight into his father’s disappearance:

“So far as I know, I am the last person to talk to him before he mysteriously disappeared off the coast of Mazatlán, Mexico in the summer of 1974, when I was 14 and in my first year of high school. I spoke with him by telephone for about 15 minutes. He said he was on his way to California in a boat with some friends. He had a bunch of drugs that he planned to sell and get rich. He would be back in a few weeks and give me a call. That was the last I or anyone heard. I did learn in the past 20 years from Irwin, a family friend, that he, Irwin, saw Oscar in northern Mexico with some other thugs in 1974 and that indeed he was making preparations to get on a boat in Mazatlán, just as Oscar told me in the phone call. Irwin said that the group somehow made their way to Mazatlán, and that things then went bad … really bad. Tempers flared, all hell broke loose. Irwin, who was not present during the last hours in Mazatlán, speculated that one of the cowards shot Oscar and killed him.”

It was a story that Thompson had also spoken of in the intervening years when questioned about Acosta’s untimely fate. As for Thompson himself, the loss of Nixon and Acosta compounded what was already a noticeable decline in the quality of his writing. By the time of Acosta’s disappearance, he had already produced his best work in Hell’s Angels, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail ’72, and though he sometimes thereafter briefly touched those heights, he could never replicate the sustained brilliance of that run of work.

As for his ministerial duties, the only evidence to be found of Dr. Thompson exercising his powers as a Doctorate in Divinity, consists of video footage of him marrying Phoebe Legere to Turbo, a prize winning bull in Aspen, which was uploaded to Legere’s official YouTube channel. According to Legere: “This is my wedding video […] You can hear The Hymen Feast, a punk song I wrote for the wedding playing under the action. The vows were solemnized by Hunter S. Thompson who was an ordained minister. He is wearing a Syrian Man’s wedding costume and a cap of unborn wolf. He toasted us with animal tranquilizers. Afterwards Turbo trotted off and I gave Hunter a blowjob. It was heaven.”

Following the 1973 Tennessee drug bust involving Muncaster and Essary and the subsequent collapse of the trial in 1974, Muncaster’s trail goes cold for several years and likewise, his accomplices from the Missionaries of the New Truth. The only other notable story in 1974 involving the Missionaries of the New Truth came on November 17th, when one Fred Weschenfelder in Montana discovered he had received a bad check. The Bozeman Chronicle reported that the check was drawn on The Missionaries of the New Truth and carried a telephone number with a 202 area code. When Weschenfelder called the number, a voice answered, “This is the White House. Who are you calling?”

It wasn’t until February of 1982 that Archbishop Muncaster once again hit the headlines, this time in relation to a multi-state investigation into benefit fraud, leading to the filing of a lawsuit in the San Francisco Superior Court by the state attorney general. According to the San Francisco Examiner, a newspaper that Hunter S. Thompson would later write a regular column for, the suit alleged “an intricate scheme to defraud the states of over $400,000 in unemployment benefits by using phony employees […] The cross-country paper chase led unemployment and Post Office investigators to two Marin residents, David Muncaster, 49, alias David Adams, and Rosalyn Bonas, 39.” Court papers claimed that Muncaster and Bonas had set up nine phony corporations, 44 Post Office boxes and mail services and 30 Bay Area bank accounts as part of their elaborate scheme that had operated for almost 5 years. The Examiner further revealed that “Five valid California drivers licenses were discovered to have been issued to Muncaster in different names” and that “the bulk of the claims were filed by Muncaster.” On June 7th 1982, Muncaster pleaded guilty to two of 41 counts against him and on September 14th, 1982, Muncaster was sentenced to four years in Federal prison for mail fraud.

In the name of full disclosure, I must confess to also being a man of the cloth, though not a member of the Missionaries of the New Truth.

On February 23rd, 2018 I was ordained into the Church of the Latter-Day Dude, a fairly straightforward process through the Church’s official website. One notable feature that presented itself in the registration process did catch my eye, however, possibly a legacy of the Rev. Larry D. Broadhead, the collie that had been ordained by The Missionaries of the New Truth. Before my application could be officially registered, The Church of the Latter Day Dude asked for confirmation that the person being ordained was not, in fact, a dog. That aside, for the bargain price of $40, I received my official Identification Card, accompanied by a letter from the Dudeocracy of the Church of the Latter-Day Dude requesting that I do not use my Identification Card “for any unlawful activities! Among other things, being a Dudeist Priest means that you’re not trying to scam anyone!” I also received a letter of good standing from Oliver Benjamin, The Dudely Lama of Dudeism, certifying that as an ordained Dudeist Priest, I am a member of “good standing of the holy order of ministers of The Church of the Latter-Day Dude.” The Dudely Lama also asks that I be recognised in my authority to “preside over any religious, sacred or ceremonial ritual, including marriage, funeral services, religious counselling, christenings, and blessings of consecration ceremonies.”

As for the Good Archbishop Muncaster, he vanished after serving out his prison sentence, though there have been numerous sightings over the years — enjoying a pint of Guinness at The Ginger Man pub in Dublin, Ireland, in the mid-’90s, holing a 30 foot putt at the Boca Royale Golf and Country Club in Englewood, Florida, sometime in 2005, with the last rumored sighting being at a dive bar in Santurce, San Juan, Puerto Rico, in March 2009 when he was allegedly seen drinking rum and enjoying a Cohiba with one Ron Mexico. If the Good Archbishop is still alive, he’d be in his 90s. We hope he is still searching for the Truth.

Link to the source article – https://www.spin.com/2023/11/hunter-s-thompson-was-a-priest/

Recommended for you

-

Army,Scout,Sea Cadet Bugle +Mouthpiece

$45,00 Buy From Amazon -

Hosa MID-315BK 5-Pin DIN to 5-Pin DIN MIDI Cable, 15 Feet

$7,95 Buy From Amazon -

Diydeg Bugle Cavalry Trumpet Brass Instrument, Military Easy to Play Trumpet C Key Brass Trumpet with Mouthpiece, Trumpet Brass Blowing Old Copper for Beginners Gift (Gold)

$47,15 Buy From Amazon -

M-Audio Oxygen 49 (MKV) â 49 Key USB MIDI Keyboard Controller With Beat Pads, Smart Chord & Scale Modes, Arpeggiator and Software Suite Included

$179,00 Buy From Amazon -

Pop Back Vocal – Large unique 24bit WAVE/KONTAKT Multi-Layer Studio Samples Production Library

$14,99 Buy From Amazon -

Blues Harmonica Real – Large original 24bit WAVE/Kontakt Samples/Loops Library

$14,99 Buy From Amazon -

Mr.Power Guitar Tuners Machine Heads 3+3 Set Tuning Keys String Pegs for Classical Guitar (Short Black, Black Button)

$20,99 Buy From Amazon -

Kalimba Thumb Piano,YUNDIE Portable 17 Keys Mbira Finger Piano with Tune Hammer and Study Instruction,Musical Instruments Birthday Gift for Kid Adult Beginners Professional(Brown)

$19,99 Buy From Amazon

Responses