Unbroken Chain: Jimmy Herring on Phil Lesh

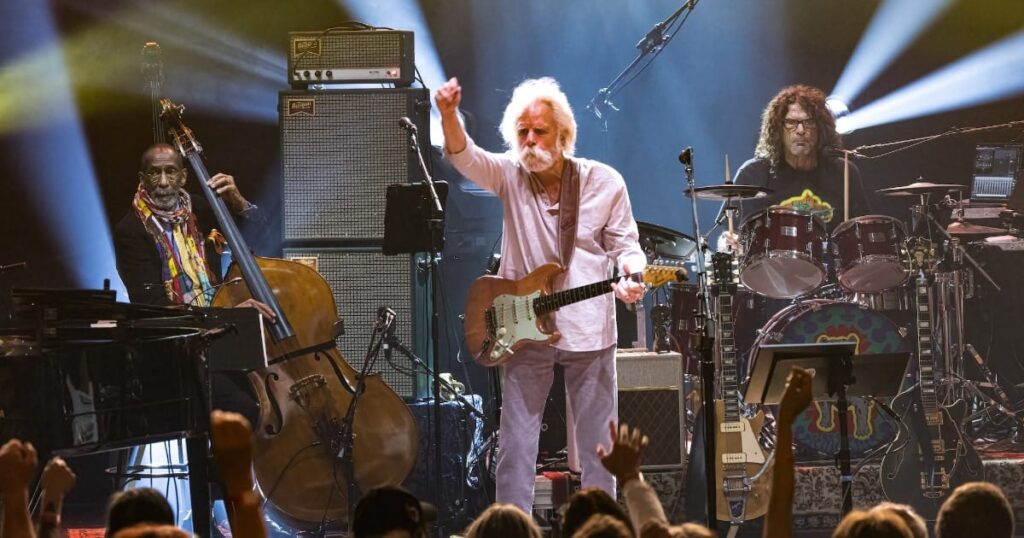

photo: Jay Blakesberg

***

In the December issue of Relix we celebrate of the pioneering bass icon’s life and career, with reflections from his friends and collaborators (as well as a previously unpublished interview), all of which we will share over the days to come…

Widespread Panic/Aquarium Rescue Unit guitarist Jimmy Herring first appeared with Phil Lesh & Friends in 2000. Two years later, he joined Lesh in The Other Ones, which also featured Bob Weir, Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann. Herring’s tenure with Lesh arguably hit its apogee with the Phil Lesh Quintet, alongside Warren Haynes, Rob Barraco and John Molo.

You performed with Phil for over two decades. It seems like he never gave up “searching for the sound.”

It’s unbelievable, man. Everybody likes to talk up their favorite musician and say there’s nobody like him, but whatever you can say about Phil, it’s all true. I mean, it can sound like hyperbole.

He’s an intellectual. Yeah, he is.

He’s got great ears. Yeah, he really does.

He hears everything.

He’s got a brilliant concept of music. His concept is very difficult to make happen, unless everybody in the band is really listening hard.

He never wants to hear people soloing. People like me and Warren grew up taking guitar solos and listening to music that inspired that, including the Grateful Dead. But Phil didn’t want that. The Grateful Dead, more than any other band I can think of, took group instrumental journeys. Yes, Jerry was soloing, but at the same time, he would leave space and the other guys would fill in that space. I read something once where somebody described the Grateful Dead, and they said: “They finished each other’s sentences. They stole each other’s lunch money.” [Laughs.] It was somewhere along those lines, and I thought it was the greatest description of the way they do it. It’s mind boggling to me how good they were at that.

Another thing about him is he never stopped. Not that long ago, back when he had the Terrapin Crossroads place, I went out there to do a show with the Quintet. We were there in the afternoon and we did a four hour rehearsal, during which Phil never sat down. I even sat down during the rehearsal— knowing that we had a show coming up—on a tall stool, so I was alert and ready to follow where the leader wanted to go. We had some time to eat when Phil did sit down, and then it was time for the show. Then after that show was over, his son’s band played and he played their whole set with them and never sat down, and I bet you there was only 15 minutes in between our show and their show.

We used to tour all the time and it was really cool. Later on, we were so lucky just to get to do a couple shows, like we did in March at The Capitol Theatre. All of us would be like, “Man, when are we going to play again?” It was just such a magic, fun time.

I guess that’s why it hit me so hard when Phil passed. The last time we played, it just seemed like there were going to be many more. In that situation, you might think people would be going, “Yeah, we better really cherish this right now because this might be the last one.” But nobody felt like that. Everybody felt it was still so vibrant and we were learning from him every moment.

I’ll never be able to put into words all the things I learned from him, and will continue learning because sometimes lessons take a while to sink in. You learn stuff from people, and sometimes it’s years later before they really start to show up in what you’re doing.

Dave Schools quoted you in saying that “Phil Lesh was the most harmonically advanced musician he’d ever played with.” Can you speak to that side of Phil?

I think what I meant was that Phil could play any Grateful Dead song in any key with no warning whatsoever. It didn’t matter what the song was, and it didn’t matter how far away from the original key. He was so sophisticated. That’s not an overstatement, what I just said about him being able to play any Grateful Dead song in any key because I worked with them through different groups of singers. At various points in the band we had Joan Osborne, Ryan Adams, Warren Haynes, Chris Robinson—all these great singers would want different keys to optimize their vocal range and I would be fumbling through it. Phil never made a mistake. Any song, any key, any day, let’s go.

Here’s another example: He had written some new music and these were beautiful little pieces. I have the charts in my book in his own hand. They were instrumental interludes, études and intros—just beautiful stuff that we would play to set up a vocal song. I remember loving these songs. But I was looking through the chart for the first time as we were rehearsing it. Then Phil stopped the band at some point, and he said, “Hey, Jimmy, can you play those chords with the fifth on the top instead of the third?” I wasn’t even aware until he said that I was voicing every chord with the third on top while I was looking through the chart. But he heard it. I’m not talking about two chords. I’m talking about a hairy chord progression that’s going through a whole bunch of different things.

I was struck because he heard it. He didn’t see it. He didn’t read it. He heard it. When you have an ear like that, you’re a musician. That, to me, is an example of what I was talking to Dave about.

When you began working with The Other Ones, did Phil have any advice for you?

When Phil asked me to do it, I said, “Phil, I don’t know all the songs.” He told me, “Yeah, you do.” I said, “But Phil, what if I make a mistake?” And he goes, “There are no mistakes, Jimmy. Just opportunities.”

That was a big takeaway. There are no mistakes, just opportunities.

He really did appreciate that uncertainty and the spontaneity of things that can happen when you don’t know where you are. It’s like when you’re walking in the dark. You might walk into a tree, you might trip over something, but then you recover and you keep going and it might put you on a different course.

This reminds me of something else. When I was with that band, Bobby Weir said to me: “We’re going to do ‘Sage and Spirit.’ So I said, “OK, I’ll be working on it.” So I started listening to the album version off Blues for Allah, and it’s a brilliant piece of music. I was learning it and when I got into rehearsal and began playing it, Bobby started laughing his ass off. I said, “What am I doing wrong?” He goes, “It doesn’t sound like you’re doing anything wrong. You’re just playing mine and Jerry’s part at the same time.”

I couldn’t tell who was who on the album. They played acoustic and they would play little fragments of the sentence, then the other guy would finish the sentence. The way the piano player Keith Godchaux filled in with Bobby and Jerry, and then Phil was doing his thing, it was almost like a Dixieland band where the fragments all sound like one line.

So, to me, it sounded like one line, but it was really a piece from Jerry, a piece from Bobby and a piece from Keith. It blew my mind that it was three different people because it sounded like one person’s thought.

That’s what Phil was looking for. He was looking for us to be able to do that. We succeeded sometimes, and sometimes we didn’t, but we tried. That was his theory, and it was brilliant.

Can you speak to Phil as a songwriter? One thing that Mike Gordon pointed out recently after Phish played “Box Rain” as an encore is that the song is more challenging than one might think because Phil didn’t like to repeat forms.

Yeah, he didn’t like to repeat the forms. Listen to “Unbroken Chain,” listen to “Box of Rain.” I had to make charts to play those songs until I played them so many times that I didn’t need it. But the charts were really helpful because each verse would be different from the last one.

We played “Pride of Cucamonga” for the first time in a really long time on one of the last two shows I played with Phil, and I’d forgotten how much I love that one. I love his writing. It’s a little hard to put into words. Bruce [Hampton] would often use that quote, “Talking about music is like dancing about architecture,” and it’s true.

I’ll say this, though, about his writing. Listen to all those songs. He loved chord progressions and he knew all that stuff cold. I could play a chord and he could tell you what it was without even looking at my hand. That’s what all musicians should strive for but he really embodied it. He liked sophisticated chords, but he liked simple chords too. He came up with highly intelligent ways of using cowboy chords—those first-position chords down by the headstock. When I was talking about those little pieces earlier, some of them had the most beautiful, involved chord progressions, but they were all simple chords. He liked simple harmony, but he found a highly intelligent way to string incredible chord progressions together. It reminds me in some ways of Pink Floyd. I mean, their vibe is completely different than Phil’s, but they’re also able to do super intelligent chord progressions with simple chords.

One of the biggest influences that Phil has had on me is that tendency. I like chords a lot. I like sophisticated chords, but most of my writing is just simple chords. For instance, the song “Lifeboat Serenade,” from my first solo record, has a bunch of chords in it but they are very simple chords. That’s what I learned from Phil, and there are a bunch of other tunes that are influenced by him.

But yeah, what I take away from his writing is his genius with chord progressions.

Although most of your Phil gigs were with the Quintet, you also played in different lineups with other players. That’s an aspect of Phil’s musical mission that remained important to him—bringing in new acolytes.

Man, it’s so beautiful. He just gave and gave and gave. I was lucky enough to be a part of some of those bands when the Quintet started not to play as much. He kept me around for a little while after that and added other people—different second guitar players, different keyboard players, different drummers and stuff like that. It was awesome.

Of course, I missed the familiarity of the Q, but it was beautiful because he was so patient. It was fun to watch people go through the PLU—Phil Lesh University.

Me and Warren talk about it all the time—everything that we’ve learned, not just from Phil directly saying things to us, but the situations he would put us in. He would put us together knowing that both of us grew up swinging the bat when it was our turn to swing and then he’d say, “No, don’t play solos.” He saw something deeper and wanted to pull out something that people hadn’t heard from you yet.

I learned from Phil that when someone takes a solo, the other musicians shouldn’t just be a backing track. He wants to hear improvisation from everybody, not just the guy taking a solo. He hated that word because he said solo implied only one. He didn’t believe that. He didn’t think of it like that.

I was lucky enough to spend a lot of years playing with Phil. From 2000-2006 there was quite a bit of playing and then it was less after that, but it was always great to get back together. I loved going back and playing with him at The Cap. There’s a vibe in that room that I really dig and playing with him there was always great. I’m going to miss that and I’m going to miss him.

So all that is what I take away from working with him. There’s a lot more, too. If you ask me on a different day, you’ll get a whole different list. [Laughs.]

Link to the source article – https://relix.com/articles/detail/unbroken-chain-jimmy-herring-on-phil-lesh/

Recommended for you

-

Banjo 5-String MINI Banjo, Lotkey Tenor Banjo Closed Sapele Back Banjo for Professional Beginners with Extra Strings Strap Pick-up Picks Tuner Bag (26-Inch)

$109,99 Buy From Amazon -

LXS Soprano Ukulele Kids Ukulele for Beginners – 21″ Small Guitar Ukulele with Gig Bag, 1 Standby String and 2 Picks (Purple)

$36,99 Buy From Amazon -

Officially Licensed Michael Anthony Jack Daniels JD Bass Mini Guitar

$40,90 Buy From Amazon -

MIDI Cable 3ft 2 Pack, 5 Pin DIN MIDI Cables 3 feet, MIDI Cord Male to Male Compatible with MIDI Keyboard Electronic Piano Electronic Drum Audio Amplifier Multi Effects Synth External Sound Card

$9,98 Buy From Amazon -

Pyle All-Weather Mono Trumpet Horn Speaker – 5â Portable PA Speaker with 8 Ohms Impedance & 25 Watts Peak Power – 180 Degree Swiveling Adjustable Bracket for Easy Maneuverability – PSP8

$17,50 Buy From Amazon -

Ernie Ball Polypro Guitar Strap, Black (P04037)

$7,99 Buy From Amazon -

Kurrent Electric (2 Pack of Type-A MIDI to 3.5mm Adapter 14″ Inch Cable

$14,99 Buy From Amazon -

SAPHUE 6 Pieces 3L3R Guitar tuner pegs,Big Square Sealed guitar tuning pegs tuners machine heads,Electric Guitar (Black) Acoustic

$11,99 Buy From Amazon

Responses